It is not inconceivable that the assassination of Salman Rushdie in New York would have happened without a prehistory that goes back to the beginning of 1989, when the Iranian Ayatollah issued a fatwa on Rushdie for blasphemy. That may sound heretical, but considering Rushdie’s intellectual engagement over the last quarter of a century, such a possibility does not at all seem like an unfounded speculation from some parallel universe. In the post-Islamic Revolution era in Iran, the world was enthralled by the way in which Rushdie wove the complexity of cultural differences into his early literature and social criticism. Rushdie was one of the few writers in the United Kingdom who dared to criticize the British intervention in the Falkland Islands. Popular, nostalgic depictions of the past of previously colonized peoples by their former colonizers were exposed by Rushdie as a new revival of old imperialist goals. Rushdie’s social criticism was sophisticated, took historical context into account, could see how the growth of colonial nostalgia in Britain coincided with the Falklands War, etc.

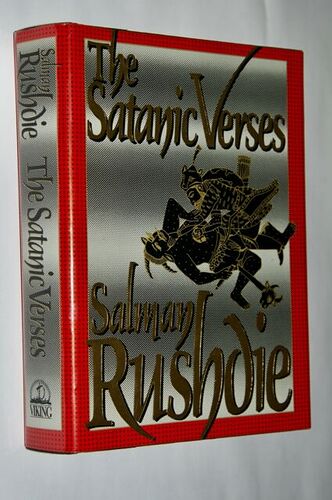

The last twenty-odd years, however, have seen the full crowning of Rushdie’s intellectual charisma and his dogmatic conformity to neoliberal political ideals, combined with the complacency that comes with celebrity status in perpetual exile. Since the end of the 1990s, Rushdie has used the public space to generalize his personal experience, arising from the “Satanic Verses” controversy, through a binary view of the world, in every way opposed to the nuanced interpretations of contemporaneity from the time of his greatest glory. Undoubtedly, Rushdie’s life in the bubble after the declaration of the fatwa, which contributed to both the narrowing of contact with the wider world and the narrowing of the intellectual perspective, gave intensity to the simplified images of reality.

For the past twenty or more years, Rushdie has used his personal tragedy for a crusade against all forms of resistance to Western neoliberalism, in which he found his new ideological refuge. He was one of the most famous names among semi-informed intellectuals in the West who strongly supported the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia and contributed to the creation of an anti-Serbian climate. He was also openly on the side of the US military in 2001 when it bombed and occupied Afghanistan. He had no understanding of the American intervention in Iraq from the point of view of weapons of mass destruction as a casus belli, but he believed that “the primary justification for regime change in Iraq is the terrible and prolonged suffering of the Iraqi people, and that the remote possibility of a future attack on America by Iraqi with weapons of secondary importance”.

Rushdie’s unconcealed action in the public sphere from the position of not only cultural, but also open political imperialism, under the guise of democracy and human rights for the last quarter of a century, no matter how conditioned it may be, cannot be reduced to his individual experience with Khomeini’s fatwa. His renegade assent to increasingly important formats of Euro-Atlantic militarism since 1999 has earned him the reputation of a belligerent, a writer who promotes aggressive wars and justifies Western imperialism.

And if it was most likely fueled by the vindictive motives of a man who was deprived of much due to the death sentence handed down by Ruhollah Khomeini, Rushdie’s long-standing apologia for militant neoliberalism has long gone beyond personal motivation and created more enemies for him than he had in the late 1980s. them, when the “Satanic Verses” were banned in Iran and the fatwa was issued. In support of this, the fact that Rushdie’s attacker from New York, Hadi Matar, is only 24 years old and was born almost a decade after the issuing of the fatwa speaks volumes.

This could easily mean that his antagonism towards Rushdie was largely shaped by Rushdie’s public attitudes with which he was a contemporary, and that the fatwa was a footnote with which he additionally tried to legitimize the terrorist act.