Archaeology in the Carribean, has advanced significantly over the past decades. Particularly in San Juan, Puerto Rico which produces more archaeologists than the rest of the Caribbean combined, with professionals now conducting research globally, from Great Britain and South America to Africa and the Middle East. This expertise is supported by a strong academic community and rigorous peer review, particularly in the States. Credit is due to archaeologists in American academia whose work after the Spanish-American War was foundational; they developed initial models to explain how Indigenous populations populated the Caribbean islands. While many of these early migration models have since been revised, they provided an essential starting point for the field.

Modern archaeology, based on materials recovered in San Juan, reveals a history of extensive interaction across regions. Evidence shows sustained contact between the Caribbean, Mesoamerica, and areas as far as the Andes. Finds such as jade statues from Guatemala and the remains of dogs dating to 2000 BC in San Juan point to a sophisticated seafaring culture. Such a culture would have required advanced knowledge of astronomy for navigation across open waters.

Notably, San Juan has 857 documented but unexcavated archaeological sites, all protected by state and federal laws. Archaeologists have intentionally left them undisturbed, primarily because the necessary infrastructure for proper stewardship is not yet in place. The region currently lacks a suitable museum, and artifacts require meticulous cataloging, conservation, and professional display. Establishing a museum involves long-term planning, sustained administration, and a dedicated budget, and some sites may eventually warrant becoming museums themselves. Therefore, the current strategy prioritizes preservation in place until adequate resources and facilities are secured for future study and public interpretation.

I am writing this after finishing a book so complex and revelatory that I feel compelled to share it. The book, El Secreto Mejor Escondido by San Juan-based researcher Roberto Pérez Reyes, is a 600-page tour de force that has genuinely raised eyebrows. Its author, notably, is an autodidact with a bachelor’s degree in Social Sciences, lacking formal advanced degrees in archaeology, geology, history, or astronomy. This monumental work is instead the product of 25 years of independent research.

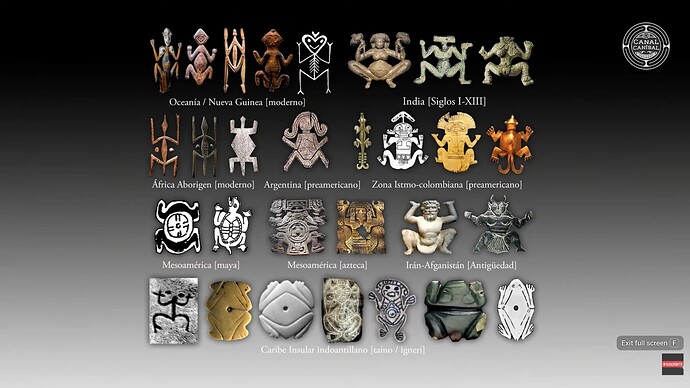

The book presents a profound study of petroglyphs across the Caribbean, centered on detailed pattern recognition of ancient symbols. Pérez Reyes’s hypothesis is that these symbols are not local curiosities but universal. He systematically demonstrates striking parallels in petroglyphs from vastly separated regions—including Mesopotamia, Mesoamerica, the Andes, the Caribbean, Africa, and Europe—and proposes they are evidence of an ancient seafaring culture. For instance, he highlights strikingly similar narratives found in Druid mythology and Indigenous Caribbean myth stories.

The work has garnered notable attention, including its inclusion in The Oxford Research Encyclopedias (OREs), which suggests it has passed a significant level of academic review, though the specific criteria for inclusion remain unclear. This combination of ambitious scope, unconventional authorship, and formal recognition makes the book particularly compelling. My mind becomes a volcano of ideas when I encounter work of this scale, and I plan to write a detailed review to introduce this complex Spanish-language work to a wider audience.

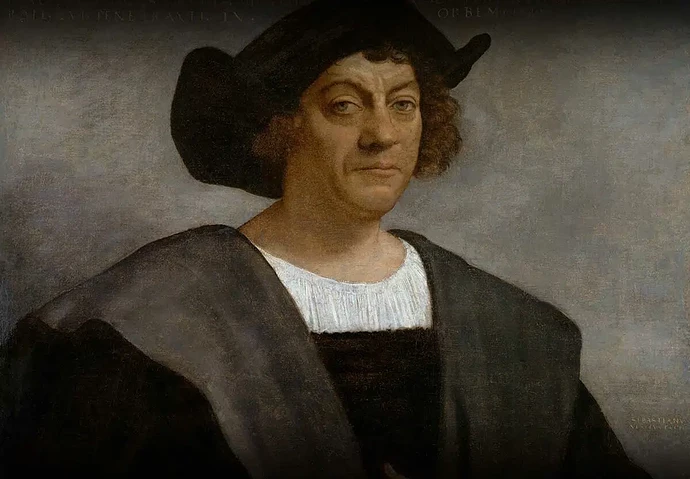

Conducting a review of this work presents a unique challenge, as it involves synthesizing a vast amount of visual material from petroglyphs with detailed historical research. Pérez Reyes does not rely on symbols alone; he anchors his analysis in primary sources, including the writings of Bartolomé de las Casas and other Spanish chroniclers, even citing observations from Christopher Columbus, who described the Indigenous people as “smart and alert.” To build his case for a sophisticated, seafaring culture, the author compiles astonishing historical accounts that defy common preconceptions.

These chronicles describe a level of maritime and martial technology that is often overlooked. For example, they record that Caribbean Indigenous societies built large ships capable of holding 200 people, using sails made of cotton. In warfare, they employed formidable armor made from densely woven cotton, three inches thick, and protected their heads with wooden helmets. These are not the artifacts of a simple or isolated people, but of a complex society with advanced material knowledge.

My task, therefore, is to bridge the author’s three main forms of evidence: the universal patterns he identifies in ancient petroglyphs across continents, Caribbean indian language and the concrete historical records that depict a highly capable Caribbean culture. The chronicles reveal ships so advanced they featured cabins and an organized system for rotating the crews paddling them, details that underscore a complex maritime tradition. The review must navigate between this symbolic language and the tangible reality it may represent. By presenting these compelling details—from colossal ships with sophisticated logistics to intricate armor—I aim to demonstrate why Pérez Reyes’s 25-year research is not only a remarkable work of autodidactic scholarship but also a provocative contribution that demands a broader academic and public conversation.

Folks, I will never ever look at Indian petroglyphs, statues, and drawings with the same eyes again. These things are deeply layered in meaning.

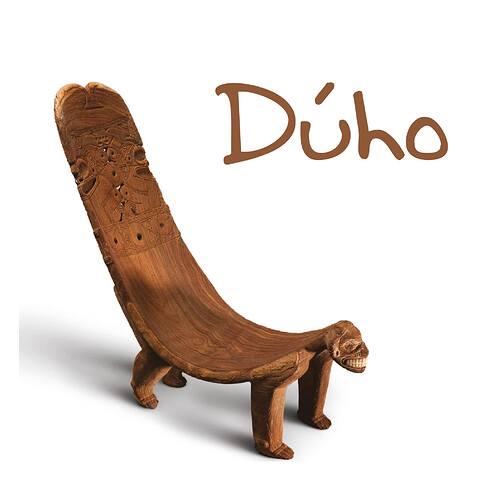

Interesting that when one studies the Indians in San Juan you come across a little artifact called the Duho. When a person sits on the Duho you naturally assume the WM position. That is the chair where the warrior sits and becomes one with the rest of the tribe and start discussing problems as a community.

Interesting that when one studies the Indians in San Juan you come across a little artifact called the Duho. When a person sits on the Duho you naturally assume the WM position. That is the chair where the warrior sits and becomes one with the rest of the tribe and start discussing problems as a community.