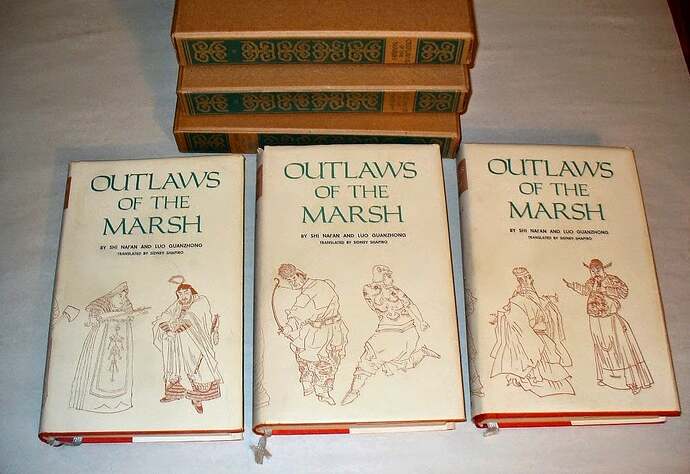

Just in case China becomes our new master, I finished reading the second volume of Outlaws of the Marsh (also known as Water Margin or All Men Are Brothers) is one of China’s Four Great Classical Novels, traditionally attributed to Shi Nai’an and Luo Guanzhong. Set during the Song Dynasty, it tells the story of 108 outlaws who gather at Mount Liang (Liangshan Marsh) to form a rebel army, fighting against corruption and injustice.

The novel follows various heroes—warriors, scholars, ex-officials, and commoners—who are forced into banditry due to the cruelty of corrupt officials. Despite their outlaw status, they uphold a code of honor, loyalty, and justice. Led by Song Jiang, they eventually accept an amnesty from the emperor and are sent to fight other rebels and foreign invaders, leading to their tragic downfall.

Outlaws of the Marsh isn’t just an adventure story; it’s a window into a radically different cultural and legal worldview, one that often clashes with Western notions of justice, individualism, and fairness. For example, in the novel one of the characters is found innocent of having murdered a woman. As a westerner you think “I guess they are going to release him then.” No!!! first he was beaten and then he was branded as a criminal on his face, then he was exiled from the province. Why? Because obviously he was a trouble maker and a problem for the community, or he never wouldn’t be suspected of a crime that heinous in the first place.

The novel made me realize how different those core assumptions are, and how different the concept of justice is. How different the concept of the balance of the individual and the collective is. In a way that we cannot even begin to have a meaningful opinion one way or the other. Is very similar to Russian culture, without understanding Orthodoxy, the role it plays, any analysis or assumption that we have is fundamentally wrong.

Here are some of the key differences in justice & social order that are present in the novel:

- Guilt by Suspicion, Not Proof

- In many traditional Chinese legal systems (especially under imperial rule), simply being accused of a crime could be enough to warrant punishment. The logic was: “A good person wouldn’t have been accused in the first place.”

- Western justice (in theory) presumes innocence until proven guilty. Chinese imperial justice often worked the opposite way—being accused was evidence of moral failing, and punishment (beating, branding, exile) served as both deterrence and social purification.

- Collective Harmony over Individual Rights

- The branding and exile weren’t just about the accused—they were about removing disruptive elements to maintain societal order. Even if innocent of the specific crime, the person was seen as a troublemaker (why else would they be involved in the situation?).

- Western individualism fights for the rights of the accused; Confucian-influenced systems prioritized stability, hierarchy, and the collective good.

- Punishment as Moral Education

- Beating and facial branding weren’t just retribution—they were public spectacles meant to reinforce social norms. The message: “This is what happens when you disturb harmony.”*

- Compare this to Western punishments, which (ideally) focus on rehabilitation or proportional retribution. Traditional Chinese justice often saw punishment as a way to “correct moral imbalance” in the cosmos, not just address the crime.

Why This Matters in Outlaws of the Marsh?

The novel’s heroes are constantly victims of this system—noble men framed, beaten, and exiled for crimes they didn’t commit, or driven to banditry because the system offers no recourse. Their rebellion isn’t just against corrupt officials; it’s against a worldview where:

- Loyalty to the group (even a bandit brotherhood) is more honorable than loyalty to a broken system.

- Violence is justified when the state itself is unjust.

- True justice comes from yi (righteousness), not laws.

Western readers might see the heroes as “criminals,” while Chinese readers often see them as “righteous rebels.” The disconnect isn’t about logic; it’s about fundamental values:

- West: Justice = fair process, individual rights.

- Traditional China: Justice = social order, moral hierarchy.

Once I grasped this, the novel’s conflicts—and much of Chinese history—make far more sense. It’s not that one system is “better”; they’re built on entirely different foundations. In the same way that Eastern Christianity is different than Western Christianity. Dr. Farrel pointed this out many times. For example, Saint Augustine is steep in the Hispanic Catholic mind. We are eternally offended for things that happened centuries ago. The Battle of San Juan in 1797 happened for me yesterday.

China’s Collectivism runs deeper than Communism. Their collectivism isn’t a product of communism—it’s a product of civilizational DNA, shaped by millennia of Confucianism, Legalism, and agrarian-state survival logic. Communism “adapted” to this pre-existing cultural framework; it didn’t create it. Many assume “China is collectivist because communism crushed individualism.” The reality is Communism succeeded in China because it spoke the language of a civilization that had always prioritized the collective over the individual.

Personally I prefer my western Catholic culture with all the Augustinian retarderies

—inherited moral culpability, the great abstractions, the ordo theologiae— is just that the idea of being branded in the face because of “the collective” is not for me. I do have Spanish empire fantasies, that said, I love the US, have Anglo family, and I’m a citizen of this nation, don’t want collectivism ruling over me. Give me the protective tariffs over collectivism.