What if the familiar story of America’s rise to global power masks a profound historical failure? This analysis, which echoes a critique pointed out by Dr. Farrell, traces the trajectory of the United States from continental expansion to overseas empire not to celebrate its triumphs, but to uncover a startling paradox: that a nation at the peak of its material strength may have achieved global dominance by bypassing the essential process of creating a genuine culture altogether.

After gaining independence in 1776, the United States began a process of territorial and technical expansion that transformed it into a continental power with maritime reach. This development occurred in distinct phases, and the most relevant aspect is that it is not far removed from us in time, allowing us to easily observe the formation of an empire from its very origins. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the war against Mexico, and the subsequent Monroe Doctrine of 1823 defined a perfectly bounded space, reserved for the United States in opposition to Europe. Initially, this space was confined to the North American continent, but it later expanded to encompass the entire continent and hemisphere.

From that point on, it was the railroad, the telegraph, and energy exploitation that consolidated the nation, fully integrating the entire territory and creating cohesion and structure. Language, culture, and state administration circulated through these infrastructures. There was a drive for unlimited dominion over space.

The Spanish-American War of 1898 was the decisive moment when the United States transitioned from a continental power to an overseas power. The conflict was triggered by the Cuban insurrection against Spain, but it was leveraged by Washington to go further and assert its power in both the Caribbean and the Pacific.

Following the disaster of the Maine —whether it was an explosion or not; if one considers the atmosphere, mindset, and public knowledge of the topic, the American public still speaks of the Maine 's explosion as something perpetrated by Spain, which is untrue—it was simply a legitimizing narrative for the events that took place, serving to divert attention toward a pretext and away from the true causes. The truth is that this accident, which occurred in Havana harbor in February 1898, was attributed to Spain without any proof whatsoever, fueled by the long-standing Black Legend propaganda of the preceding centuries in the Anglo-Saxon world. From that point, Spain was assigned responsibility without any evidence.

The U.S. Congress declared war, and the conflict lasted practically 120 days. It concluded with a complete Spanish defeat. The Treaty of Paris in December 1898 established peace terms that were not especially substantial in the American context but were the final blow for Spain, which was approaching the beginning of what would become its definitive abyss. Spain recognized Cuba’s independence, ceded Guam, ceded San Juan (where there had never been any rebellion or similar unrest), and surrendered the Philippines in exchange for $20 million—the alternative was to receive nothing.

With these acquisitions, Washington secured a strategic position in the Caribbean and opened the door to the Pacific and Asia on the other side. The War of 1898 was much more than a simple colonial conflict because it marked the entry of the United States into world politics as a power with overseas territories and strategic bases. It is the first time one can truly say that the United States was a power participating in world politics. From that point, all the foundational elements for the formation of the empire were in place.

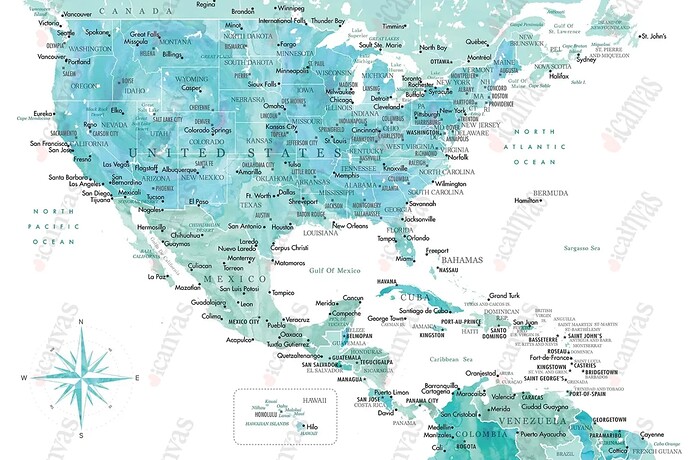

Control over Cuba was secured through the Platt Amendment of 1901, which granted the United States the right to intervene in the island’s internal affairs and guaranteed the perpetual lease of the Guantanamo Bay naval base. Although Cuba was formally declared independent in 1902, its sovereignty was limited by American guardianship. This was not a sovereign nation, as its decisions and its capacity to determine its own will were ultimately dependent on Washington’s. To claim that Cuba was an independent country in 1902 is, to put it mildly, a bit of an overstatement. San Juan, on the other hand, came under direct control and was transformed into an unincorporated territory under Washington’s sovereignty. These measures ensured the United States a dominant position in the Caribbean, the routes to the Panama Canal, and access to the Atlantic Ocean.

The construction of the Panama Canal, completed in 1914, solidified the transformation of the Caribbean into a U.S. inland sea. The need for an inter-oceanic passage had been discussed since the mid-19th century. Then, in 1903, after supporting Panama’s independence from Colombia—another event we can mark as a milestone in the empire’s formation—the United States obtained control over the zone where the canal would be excavated. The work was carried out between 1904 and 1914, creating a connection between the Atlantic and Pacific under direct U.S. administration. From that moment, the canal became a cornerstone of Washington’s naval and commercial strategy, ensuring fleet mobility and primary control over the inter-oceanic route. In geopolitical terms, the canal made the Caribbean an indispensable space for U.S. security and power projection.

An important observation: Cuba is the United States’ Ukraine. It is an element that the U.S. cannot do without, as its loss would represent a threat to its vital interests in what can practically be considered an inland lake—the Caribbean Sea. This explains why, precisely at this time, the theories of Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan (shown in picture) were being implemented through Theodore Roosevelt. Upon becoming president, Roosevelt initiated the canal’s expansion and built the immense U.S. fleet, using this naval power to control the waters and guarantee the primacy of its maritime power and command over commercial routes.

During this period, and using the theories of Graham T. Allison as a reference, the succession of hegemony takes place over the following decades. It passes from the British Victorian Empire to its successor, the former colony of London, which would establish itself as the new international power by controlling the seas. This transition began around 1914 and concluded more or less shortly after the end of the Second World War in 1945.

The period between 1898 and 1934 was marked by a series of military interventions in the Caribbean and Central America known as the Banana Wars. In 1906, U.S. Marines landed in Cuba to quell political unrest. They did so again in Nicaragua in 1912. In 1915, they intervened in Haiti, remaining until 1934. In 1916, they occupied the Dominican Republic until 1924. These interventions were justified as efforts to guarantee order, protect legitimate economic interests, and ensure the repayment of debt to external creditors. But in reality, they were part of a strategy to consolidate control over the Caribbean and Central America. To guarantee its security, the United States necessarily must control the entire northern coast of South America. The geographical areas of Venezuela and Colombia are absolutely strategic and vital for maintaining U.S. power and control on the continent. This is what guarantees its control and hegemony over the “American island.”

In Haiti, the occupation allowed for the reorganization of the army and finances under American supervision. In the Dominican Republic, Washington established a protectorate—it was nothing less than a colony. In Nicaragua, the intervention lasted until the 1930s with the presence of troops and military advisors. In Honduras, interventions were recurrent to guarantee the influence of American banana companies. This entire set of military operations consolidated U.S. dominance over the Caribbean arc and Central America, ensuring that no European power could establish itself in the region and that local governments remained subordinated to Washington.

All of this is crucial for understanding the events we are witnessing today. Beyond ideological questions of left and right, understanding the deep-seated reasons that might drive Washington to act in Venezuela, requires this prior knowledge.

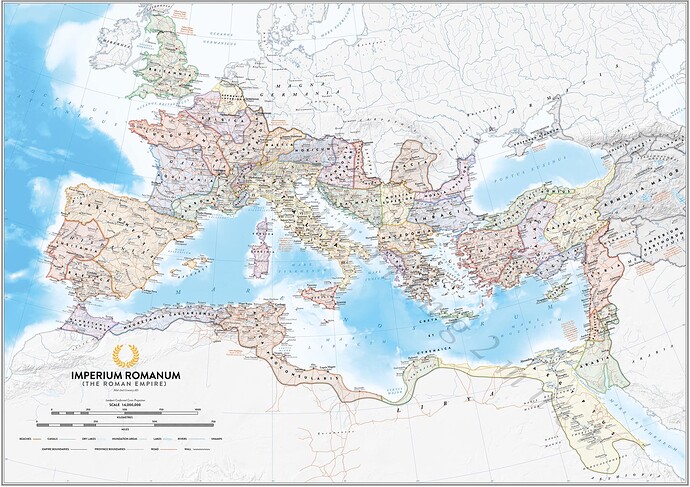

From a doctrinal point of view, the Caribbean became the American mare nostrum (our sea). The comparison with Rome is not an exaggeration but is quite accurate. After defeating Carthage and controlling Greece and Asia Minor, Rome turned the Mediterranean into its inland sea and the foundation of its empire. Similarly, after the war of 1898 and the interventions of the first decades of the 20th century, the United States closed the Caribbean to rival powers and transformed it into an interior maritime space. The control of the islands, the construction of the canal, and the network of military bases ensured complete command of the Caribbean basin.

It is important not to see the Caribbean as a peripheral geographical area. Rather, it was conceived as a cornerstone of American security. Whoever controlled the semi-enclosed Caribbean Sea dominated inter-oceanic communications and could protect the Gulf of Mexico coastlines and the vital outlet of the Mississippi River, the lifeblood of the nation’s economy. In this way, the transformation of the Caribbean into the mare nostrum was the indispensable prerequisite for the United States’ assertion of itself as a global power. If we were to identify a single point in the architecture of American global power, have no doubt: the axis and the cornerstone of that architecture is the Caribbean.

Control of the canal, and therefore of the sea lanes, is what allowed Washington to project power into the Pacific and complete the transition from a purely continental power to an oceanic one. This process is part of the civilizing trajectory of a power that, after exhausting its interior expansion, needs to organize its maritime space. Carl Schmitt, in The Nomos of the Earth , described the Caribbean —once it was closed off by the United States— as an open space transformed into an exclusive hegemony. In both cases, the logic of a “great space” prevails. The continental land conquered by the Manifest Destiny found its perfect complement in the control of the Caribbean Sea, thereby securing this inland sea.

In summary, the 1898 war against Spain, the construction of the canal, and the Caribbean interventions consolidated the American mare nostrum . This represented a series of events that begun with the Monroe Doctrine and prepared the leap into the Pacific through the archipelagoes of Hawaii, Guam, the Philippines, and Wake Island, which would become pieces of a new oceanic order under American control.

In 1890, US census declared that a continuous frontier line no longer existed anywhere, symbolizing the exhaustion of continental space for expansion. There was simply no more land to conquer. This, coupled with the victory in the Spanish-American War and the newfound control over the Caribbean, channeled that American vital energy and force toward the Pacific. Expansion across the Atlantic was not a viable option, as the other side was occupied by the world’s main powers in the Eurasian peninsula. Logically, the softer, weaker, and more accessible path was Asia. The subsequent expansion into the harder, more central part of the world—the Eurasian peninsula—would come later.

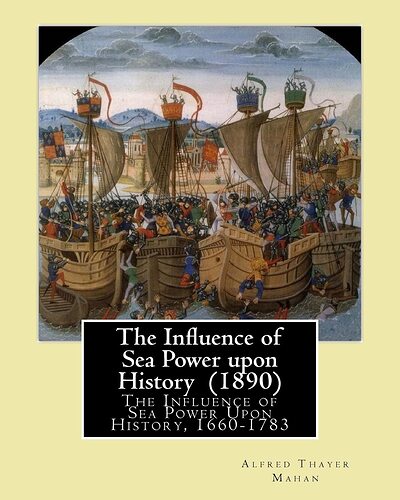

Having completed its continental expansion, secured victory in Cuba, established control over the Caribbean, the creation of an inter-oceanic canal that facilitated the movement of the naval power between oceans, the United States embarked on an expansion that had to be projected across seas and archipelagos. In my opinion, they followed the doctrine of Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan, the naval theorist who wrote a book called The Influence of Sea Power upon History in 1890. Mahan emphasized that sea power was the key to global hegemony. In order for the United States to possess all the necessary elements to become a world power, it had to follow the maritime route, which was the vehicle for reaching the rest of the world.

The first concrete step in realizing Mahan’s idea was the annexation of Hawaii in 1898, the same year the Spanish American war ended. From my reading of this history, American influence in Hawaii had been growing since the mid-19th century through Protestant missionaries. This highlights the importance of religious penetration; religion often provides the framework for the beginning of a process of subjugation and invasion. We see this today with the expansion of the evangelical movement into South America, and it also occurred in the Philippines, where Protestant missionaries began to settle and convert the population. Additionally, sugar planters and merchants trading between the American continent and Asia began to establish themselves there.

In 1893, a coup supported by U.S. forces deposed the Queen of Hawaii, Liliʻuokalani, and established a provisional government. Notice the curious pattern: the new government promptly requested annexation with the United States. The importance of Hawaii was logical; it was located in a strategic position at the center of the Pacific. What began with Protestant pastors, merchants, and sugar planters ended with the Marines and culminated in Hawaii becoming a U.S. state. Thus, the United States needed Hawaii as an essential point for controlling the entire Pacific Ocean. From there, it could project power north and south, deny access to the continent, and it has always served the function of guaranteeing the American presence in Asia.

In a short span of time, the United States had transitioned from a purely continental power to one with a presence on two continents. Furthermore, it did so by establishing intermediate points between them, thereby projecting its power from the Atlantic coasts of Europe and Africa to the Asian coasts of the Pacific. It was projecting a fully global, planetary presence.

During this period, a technocratic movement emerged, championed by a man named Howard Scott, an engineer without formal qualifications. Since the 1920s, he had argued that capitalism was doomed to collapse because technical advancements had made economic regulation through monetary prices unviable. In 1932, Technocracy Incorporated was founded. This organization proposed replacing the monetary system with an energy-based system.

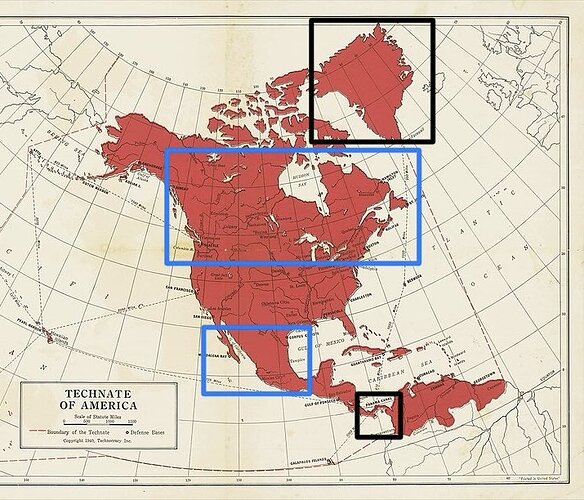

The central idea was that every citizen would receive purchasing rights and power equivalent to the energy production of the system, measured in physical units like joules. In this way, value would be detached from money and linked directly to the technical capacity to generate energy and goods. The project was called the “Technate of America” and was conceived as a continental entity encompassing Canada, Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean—in essence, the intimate North American space.

From the perspective of U.S. doctrine, the independence of Mexico or Canada are mere tolerable fictions, not independent realities. We constantly see that they are peripheral countries to the United States, dependent in all aspects—economic, commercial, cultural, and military—on the will of Washington. From a geopolitical standpoint, they cannot be said to have a life of their own. In some conceptions, this idea even extended to Greenland (involving Denmark) and the northern part of South America. Very similar to what we see now with President Trump wanting annex Canada and purchase Greenland.

This technocratic movement argued that monetary control, through the lens of energy, had to be governed by technical bodies of engineers rather than parliamentary assemblies. These technical bodies would be organized into departments responsible for production, transportation, communications, and health. The guiding principle of this entire system was that technology and energy constituted the real basis of social life; therefore, politics should be replaced by a scientific administration of space. It resembles something like the “Government of the Sages” from classical Greece.

This cannot be viewed as merely an isolated project of engineers living in a utopia. In my opinion, it is the expression of a very important historical process. After having closed its territorial expansion and secured control over the Caribbean and the Pacific, the United States had configured what Carl Schmitt termed a “great space” (Großraum)—a closed realm, self-sufficient in resources and shielded from external influences. These are the prerequisites of a “great space” as Schmitt defines it in The Nomos of the Earth .

The technocratic utopia is the next logical step: the idea that this “great space” could be administered like an energy machine, eliminating politics and subordinating all social life to purely technical criteria. This is a symptom of a country that has abandoned the phase of “culture” to enter fully into the phase of “civilization,” where the technical and the economic take precedence over all other aspects of existence. It is the first symptom of the crystallization, or the rigid structuring, of the United States.

We are speaking of a period, where the United States had only just formed and was ascending to the peak of its imperial expansion. Yet, at that very moment, a phenomena appears that is characteristic of cultures that have already developed through their entire phase of ascent and zenith, and which have lost that vital force for expansion.

What does this lead me to conclude? The United States has never, ever, ever constituted a true culture. Simply put, the United States skipped from a phase of ascent directly into a phase of civilization.

This is characterized by the predominance of technique, the predominance of bureaucracy, the predominance of administration. It is an attempt to maintain what already exists, but it lacks any creative force. If you observe Americans, they go to Europe and buy a cathedral’s iron gate; they dismantle a medieval monastery and ship it home. They travel to Europe yearning to acquire a content of culture, of high culture, which they themselves lack. Everything generated in the United States comes from a position of civilization—from a loss of form and an amorphous perspective. All it has done is prolong itself in time because it no longer possesses any vital force.

Let me put it subtly. Who are the protagonists of all this?

-

Who were the protagonists of the railroad’s construction?

-

Who were the protagonists of the communications networks?

-

Who were the protagonists behind the creation of the Federal Reserve?

-

Who were the protagonists of the rise of Hollywood, which presents an American imaginary lifted directly from the Old Testament?

-

Who represents the movements of high finance on Wall Street, which suddenly surged to lead the world alongside the City of London?

-

Who were the authors of the Frankfurt School who relocated to the United States?

-

Who leads the counter-cultural movements?

-

Who controls the pornographic industry?

-

Who dominates the information and communication systems in the United States?

-

Who practices critical theory?

-

Who is behind all the movements for egalitarianism and civil rights?

-

Who mobilizes against the imperial aspect of expansion?

-

Who are all these people?

And if we think about it, this phenomenon is associated with a corrupting and parasitic role upon what could have been a different cultural model—a model that was, however, completely hollowed out and sterilized from its origin. And that is why it can never become a high culture capable of acting as a classical canon projected onto others. There is no Rome. There is no Greece. There is no British Empire. There is no Spanish Empire. There is no model of Louis XIV’s France. There is no model of imperial Japan.

It represents nothing more than a single word: cosmopolitanism.

It is a people who belong to no particular place (citizens of the world), who put down roots nowhere, and whose kingdom is the kingdom of the material—of consumption, sensuality, hedonism, and money. Their power is based on wealth, and their greatness is based on the possession of goods, not on the generation of a high culture.

This phenomenon is what helps us understand the point we have reached. In my opinion, America is not a dead nation, it simply needs to become one.