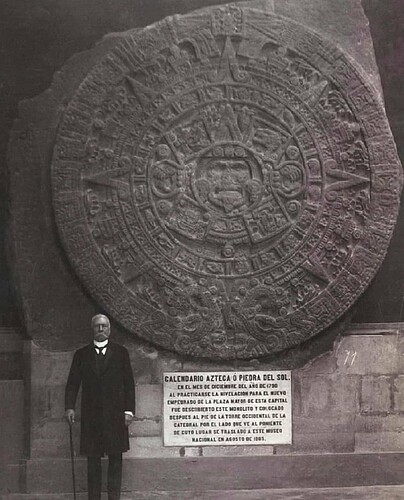

Imagine standing before the Aztec Sun Stone, an enormous basalt disk intricately carved with hieroglyphic symbols representing the Aztec creation myth and what appears to be calendar signs. Now housed in the National Anthropology Museum in Mexico City, this masterpiece is often referred to as the Aztec Calendar Stone, though its true purpose remains debated. Some anthropologists suggest it was not a calendar but a sacrificial platform, where warriors’ blood was offered to the sun god Tonatiuh, whose face dominates the center of the stone. Measuring 3.58 meters (11.75 ft) in diameter, 98 cm (3.22 ft) thick, and weighing around 24 tons, this extraordinary artifact is believed to have been carved between 1502 and 1521. Over time, its powerful imagery has been embraced as a symbol of Mexican and Chicano cultural identity, appearing in folk art, murals, and modern expressions of heritage.

.

.

.

.

.

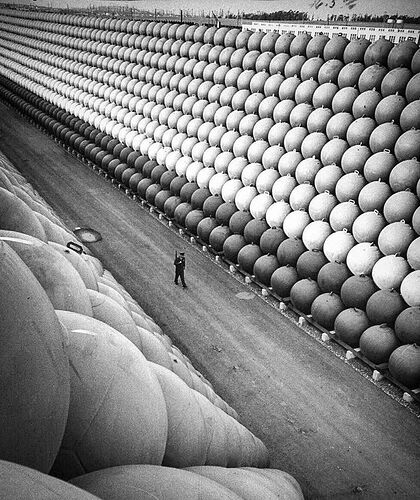

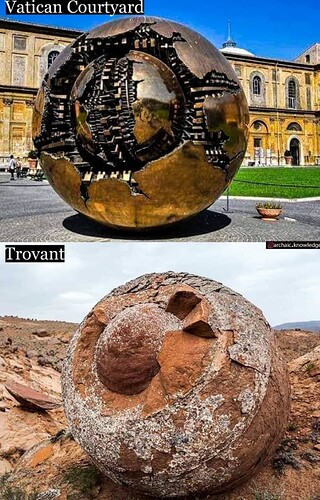

Imagine standing before a gleaming bronze sphere in the heart of the Vatican, and sensing something eerily ancient about its form. This modern sculpture, crafted by Italian artist Arnaldo Pomodoro and titled Sphere Within Sphere, bears a strange resemblance to the natural trovants—Romania’s enigmatic “living stones.” While Pomodoro’s creation symbolizes a fractured Earth and the spiritual birth of a new world, trovants are geological curiosities formed over millions of years, with mineral shells enveloping ancient organic fossils. Crack one open, and you might uncover remnants of long-lost life. Though one is human-made and the other a product of deep time, both share a layered design and evoke mystery: one tells of war and rebirth, the other of life entombed and preserved. It’s as if nature and art are mirroring each other, each holding hidden truths at their core.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Canyon de Chelly, Arizona, 1900.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

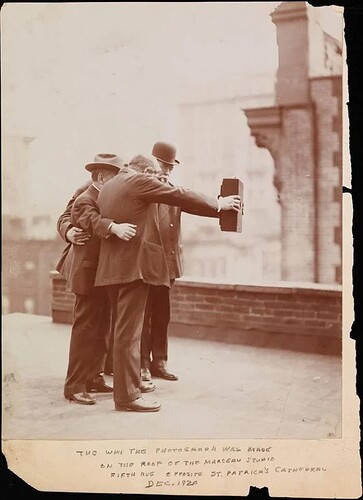

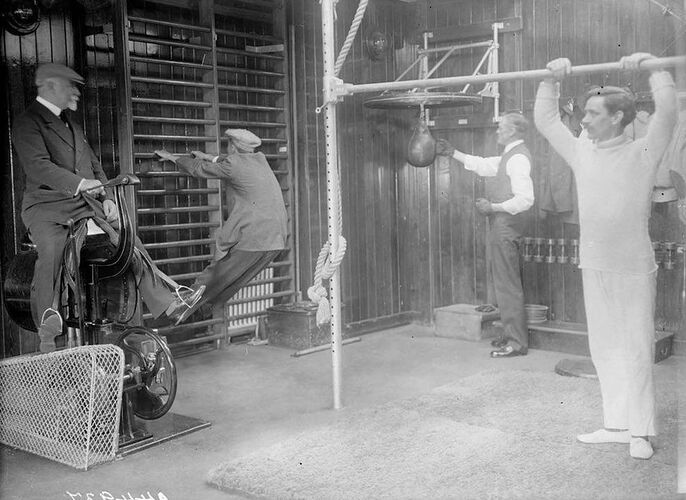

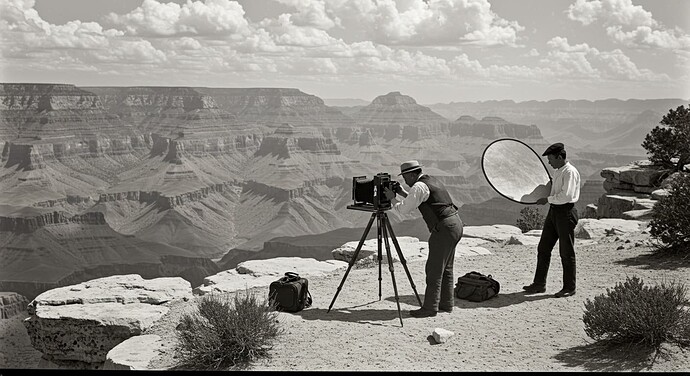

In 1908, a photographer and his assistant stand on the edge of the Grand Canyon, Arizona, balancing skill and courage to capture the perfect shot. With a bulky large-format camera mounted on a tripod, every frame required meticulous setup—measuring light, adjusting focus, and often waiting hours for the right conditions. The assistant likely hauled heavy glass plates, chemicals, and equipment across rough terrain. Dressed in period attire—vests, hats, and boots—they worked at the intersection of art and exploration. Their efforts preserved not just an image, but a moment in the early story of American landscape photography.

.

.

.

.

.

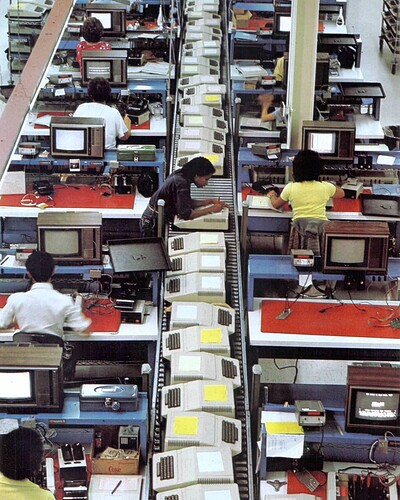

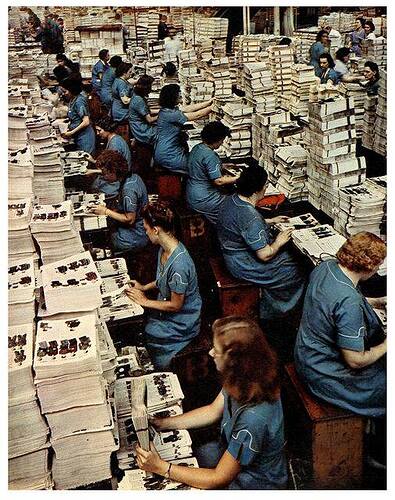

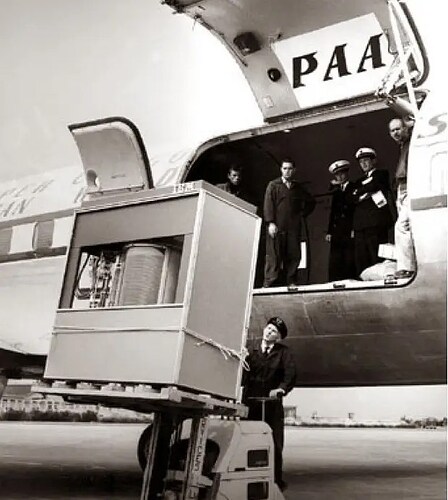

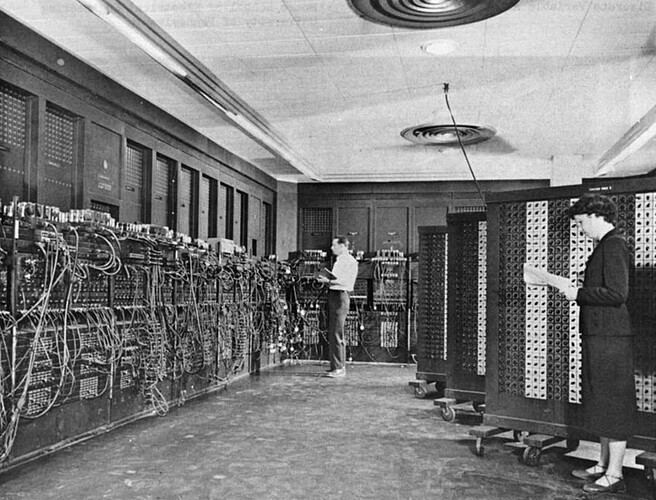

Imagine a world where complex calculations took days to complete manually. It was in this context that ENIAC emerged in 1946, revolutionizing computing as the first large-scale electronic computer. Created by John W. Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert at the University of Pennsylvania, its primary purpose was to speed up military calculations, such as those used in ballistics.

Programming the ENIAC was a true challenge: six pioneering women, known as the “ENIAC programmers,” had to manually connect wires and adjust switches to configure each new task. Additionally, the machine used punch cards to store information, a common method at the time.

With 17,468 vacuum tubes, occupying 167 square meters, and weighing 30 tons, the ENIAC performed 5,000 operations per second, an astonishing achievement for its era. Though primitive compared to modern computers, it marked the beginning of the digital age, paving the way for the innovations that shape technology in our daily lives today.

.

.

.

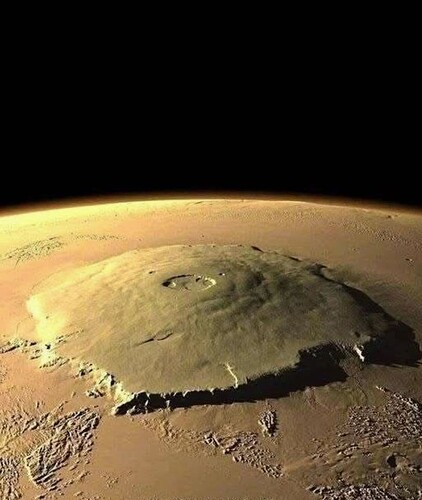

Olympus Mons, a massive volcano on Mars, stands as the tallest mountain in our solar system. Towering 26 kilometers (16 miles) high and stretching 600 kilometers (373 miles) wide, it dwarfs Earth’s Mount Everest by nearly three times.

.

.

.

.

The Stair of Death: The Inca’s Daring Pathway in the Clouds

High in the Peruvian Andes, where the air is thin and the mountains rise like stone sentinels, lies one of the most treacherous remnants of the Inca Empire—the “Stair of Death.” This perilous staircase, carved directly into the mountainside over 600 years ago, is a testament to the engineering brilliance and fearless spirit of the Inca civilization.

Part of the steep ascent to Huayna Picchu, the towering peak overlooking Machu Picchu, these ancient stone steps demand unwavering focus from those who dare to climb them. With near-vertical inclines, sheer drop-offs, and no modern safety measures, the journey is not for the faint of heart. Yet, for those who brave the climb, the reward is breathtaking—a panoramic view of the lost city of the Incas, nestled among the clouds.

Though the name “Stair of Death” adds an air of foreboding, many adventurers successfully conquer the climb each year. The Incas, masters of stonework and mountain travel, built these steps with remarkable precision, ensuring they withstood centuries of erosion. Their design, however, reflects a civilization accustomed to living on the edge—both literally and figuratively.

Was this treacherous path a sacred pilgrimage? A test of endurance for the Inca elite? Or simply a shortcut for those who ruled from the mountaintops? Whatever the case, the Stair of Death remains an awe-inspiring relic, a silent challenge to all who seek to follow in the footsteps of the Incas.

.

.

.

.

Imagine standing before a throne that has witnessed the rise of emperors, a silent sentinel to centuries of power and tradition. This is the Throne of Charlemagne, an austere yet profoundly symbolic seat located in Aachen Cathedral. For more than five centuries, from the coronation of Charlemagne in 800 AD until 1531, it was the coronation throne of the Kings of Germany, playing a central role in thirty-one royal ascensions.

Constructed from simple marble slabs held together by bronze clamps, the throne’s unadorned design only adds to its mystique. Some believe the stone may have been repurposed from an even older structure, possibly the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, linking it to the sacred legacy of Christian kingship. Positioned high above the cathedral floor, it was not only a seat of authority but a powerful statement of divine rule.

Today, the Throne of Charlemagne remains one of the most revered artifacts of medieval Europe, standing as a testament to the political and religious influence of the Holy Roman Empire. Its worn surface and timeworn presence whisper of the kings who once sat upon it, their reigns echoing through the corridors of history.