I want to preface this with a note of nuance. I speak from a particular vantage point: I was born in San Juan, a descendant of Spaniards who have lived on the island for centuries, and I am also an American citizen. I have a deep appreciation for both the Anglo-Protestant and Hispanic cultural traditions. My intention is not to frame this in reductive, dualistic terms, but to suggest that each possesses a distinct kind of genius—one is not superior to the other, but they are fundamentally different in their orientation.

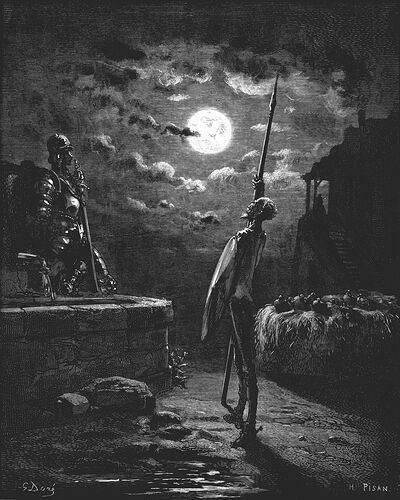

Growing up, I often noticed that many homes I visited — whether belonging to friends or family — had a copy of Don Quijote on display, or a painting inspired by its story. You’d even see a portrait or small statue in the waiting rooms of doctors’ offices, as though it were a quiet, shared touchstone. My uncle, for instance, keeps a large painting of Don Quijote tumbling off his horse. He once told me he appreciates it not just as art, but as a kind of personal reminder—a visual lesson in staying grounded. To him, the image speaks gently about humility, about embracing life’s stumbles with grace, and valuing the sincerity of the effort as much as the outcome. It’s never been just decoration; it’s something more like quiet companionship—a familiar, cultural anchor that feels both personal and universal.

To regard Miguel de Cervantes as mere literature is to miss its true significance; it is, in fact, the cosmology for the Hispanic way of life. The virtues it exalts are our virtues. That heroic, Homeric spirit is our spirit. The Hispanic civilization, in this profound sense, is defined by a sacrificial, heroic ethos.

There is a legendary quote that encapsulates this, comes from Part 1, Chapter 5, in Don Quixote:

“I know who I am.”

“I was born, by Heaven’s will, in this our iron age, to revive the age of gold. I am he for whom are reserved all dangers, all valiant deeds, and all great feats.”

The Anglo-Protestant worldview, for all its power, is ultimately a cosmology of the individual self—its rights, its prosperity, its salvation, its constructed identity. The Hispanic spirit, as channeled through the cosmology of El Quijote, is about something far more profound: it is a cosmology of the Soul. This isn’t about individualism versus collectivism; it’s about the individual’s relationship to a transcendent, eternal drama of honor, destiny, and sacrifice that gives life its deepest meaning.

The Anglo worldview asks, “What can I build?” and “What is my right?” It is a horizontal negotiation between the self and the world, measured in material outcomes and personal liberty. It is powerful, effective, and clear-eyed. But the Quixotic spirit asks a more vertical, daunting question: “What is worthy of my sacrifice?” It is not concerned with building a prosperous life for the self, but with burning up the self in the service of a transcendent ideal—be it God, Honor, Family, La Patria, etc. This is why failure is not defeat; the world’s judgment is irrelevant. The value is located in the purity of the intention and the grandeur of the struggle itself. This is the spirit that could march into a jungle not to extract resources or build an efficient plantation, but to plant a cross, to found a city in the name of God and King, to inscribe a fragment of eternal civilization onto the savage chaos of the world, regardless of the cost. That is not individualism; it is a form of sacred, heroic participation in a cosmic order.

Sometimes I’ve come to view the relationship through the lens of Cervantes’ great duo: if the Anglo-Protestant tradition embodies the pragmatic, material-minded wisdom of Sancho Panza—focused on building, prospering, and navigating the world as it is—then the Hispanic tradition embodies the quixotic spirit of Don Quijote—driven by a quest for transcendent ideals like honor, faith, and the soul’s destiny, often against all pragmatic odds. And just like in the novel, both are essential; the world needs both the dreamer and the realist.

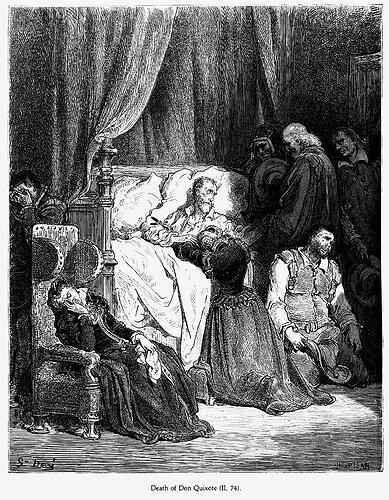

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, absolutely saw the emerging, disenchanted, materialist world coming, is a monumental lament and a resistance against it. Don Quixote dying when he recovers his sanity is the ultimate proof. Cervantes is telling us that in this new, “sane” world they are building, there is no place for the Quixotic spirit. The moment Alonso Quijano the Good accepts the world as it is—a world defined by pragmatism, calculation, and cold reality—he must necessarily die. His soul cannot inhabit such a world.

Cervantes was diagnosing a spiritual sickness at the very moment of its birth. The Hispanic way, through the Quixotic lens—with its focus on soul over matter, sacrifice over success, honor over profit, and noble failure over mediocre victory—is indeed the antithesis of the materialist, enlightenment, disenchanted worldview that would come to dominate the modern age. Don Quixote is not just a funny story about a madman. It is a tragic prophecy.

We failed. Hispanic civilization, in a sense, fell off its horse just like the Quijote in my uncle’s painting. The enduring Christian virtues that once ordered our world were gradually displaced by imported Enlightenment abstractions, civil wars. There is still a foundation to rebuild upon—not a replica of what was, but something that remembers its character.