The Second Coming of Saturn Part 18: The Mount Hermon Inscription

January 9, 2022 by Derek Gilbert

Share this!

The work of archaeologists continues to confirm the account in the Bible. A new, just-published translation of an inscription discovered about a hundred and fifty years ago inside a temple on the summit of Mount Hermon adds more support for the theory that this entity, under a variety of names, has had a profound influence on human history and will play a devastating role before the final battle of the ages, Armageddon.

Sir Charles Warren, who later led the investigation into the Jack the Ripper murders

In September of 1869, a British military engineer and explorer named Charles Warren climbed to the summit of Mount Hermon on behalf of the Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF). The PEF was founded in 1865 under the patronage of Queen Victoria. The society included some of the giants in the field of archaeology, such as Sir William Flinders Petrie, Claude Conder, T. E. Lawrence (“of Arabia”), Kathleen Kenyon, and Sir Leonard Woolley,[1] who excavated Ur in the 1920s. It’s no coincidence that many of those sent into the field had military training; by the second half of the nineteenth century, the Ottoman Empire was crumbling and the great powers of Europe had their knives out, ready to carve up its carcass. We’ve learned a lot about the ancient world from the work of men like Warren, Petrie, and Lawrence, but the British government collected useful intelligence at the same time.

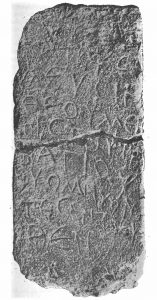

On top of Hermon, more than nine thousand feet above sea level, Warren visited an ancient temple called Qasr Antar, the highest man-made place of worship on the planet. It was probably built during the Greek or Roman period, placing its construction in the third century BC at the earliest. Inside the temple, Warren found an artifact that had been overlooked by visitors for two thousand years—a stela, a limestone slab about four feet high, eighteen inches wide, and twelve inches thick, with an inscription in archaic Greek:

A later attestation of the sacred character of Mount Hermon appears in an enigmatic Greek inscription, perhaps from the third century C.E., which was found on its peak: Κατὰ κέλευσιν θεοῦ μεγίστου κ[αὶ] ἁγίου οἱ ὀμνύοντες ἐντεῦθεν (“According to the command of the greatest a[nd] holy God, those who take an oath [proceed] from here”).[2]

The Watcher Stone, found in a temple on the summit of Mount Hermon (click to enlarge)

Because the inscription is Greek rather than in a Semitic language like Aramaic, Hebrew, Canaanite, or Akkadian, the stela can’t be dated earlier than Alexander the Great’s invasion of the Levant in the late fourth century BC. Scholar George W. E. Nickelsburg, who’s produced a modern translation of the Book of 1 Enoch and a detailed commentary on the book, connects the inscription to the Watchers of Genesis 6, whose mutual pact on the summit is described in 1 Enoch:

Shemihazah, their chief, said to them, “I fear that you will not want to do this deed, and I alone shall be guilty of a great sin.” And they all answered him and said, “Let us all swear an oath, and let us all bind one another with a curse, that none of us turn back from this counsel until we fulfill it and do this deed.” Then they all swore together and bound one another with a curse. And they were, all of them, two hundred, who descended in the days of Jared onto the peak of Mount Hermon.[3]

The stela is currently in the possession of the British Museum, which it received from Warren in 1870, after some difficulty in wrestling the two-ton slab of limestone down the mountain.

For some reason, the stone wasn’t unboxed until 1884, and then, because of questions over its origin, it wasn’t translated until 1903. Renowned French orientalist Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau, who worked with Warren to obtain the Moabite Stone, interpreted the Greek inscription this way:

By the order of the god most great and holy, those who take the oath—hence

Like Nickelsburg, Clermont-Ganneau linked the stone to the Watchers’ rebellion on Mount Hermon. In fact, he devoted some pages to Enoch’s account of the Watchers in the same edition of the Palestine Exploration Fund’s Quarterly Report for 1903, and came to an eye-opening conclusion:

Now, whether justified or not, this popular tradition existed in ancient times: Mount Hermon was the “mountain of oath.” [5] (Emphasis added)

In an earlier article, we discussed the Hurrians of Shechem who worshiped Baal-berith, “lord of the covenant.” It’s possible that Baal-berith, the “lord of the covenant” worshiped at Shechem, was not the Indo-Aryan deity Mitra, but Baal-Hermon—that is, the “lord of Hermon.”

And this is where things get interesting. Thanks to new research by our friend, Dr. Douglas Hamp, we can connect the dots between Mount Hermon and the rebellion of the Watchers led by Shemihazah, El, Dagan, and Enlil.

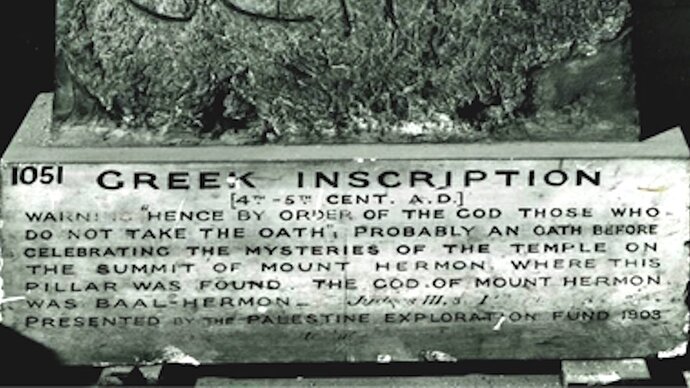

Doug noticed that accepted translations of the “Watchers Stone” appear to gloss over a couple of words. For example, the text on the base of the stone, when it was displayed at the British Museum, reads:

Greek Inscription

[4th–5th Cent. A.D.]

Warning: “Hence by order of the god those who do not take the oath”; probably an oath before celebrating the mysteries of the temple on the summit of Mount Hermon, where this pillar was found. The god of Mount Hermon was Baal-Hermon—Judges III, 3

Presented by the Palestine Exploration Fund, 1903

So, we’ve seen three translations of the inscription:

- Nickelsburg: “According to the command of the greatest a[nd] holy God, those who take an oath [proceed] from here.”

- Clermont-Ganneau: “By the order of the god most great and holy, those who take the oath—hence!”

- British Museum: “Hence by order of the god those who do not take the oath.”

That’s not exactly a consensus, but the bigger issue, Hamp contends, is that the Greek transcription on which those translations are based is flawed.

Words five and six βο bo and βατιου batiou are mysterious which could be why they were completely ignored by the British Museum, and amended by Nickelsburg; βο bo “a(nd)” and βατιου batiou as άγιου [b]hagiou.[6]

So, to compare, here is Nickelsburg’s translation (my emphasis):

Katá k élefsin theoú megí stou k[a í ] agíou oi omnýontes entefthen.

Now, Doug Hamp’s rendering:

Kata keleusin theou megistou bo batiou ou omnuontes enteuthen.

Rejecting the reading by Clermont-Ganneau and Nickelsburg, Hamp proposes to read bo as a Greek prefix meaning “bull, ox, male cattle.”[7] He suggests that this fits with the bull imagery associated with Baal (Hadad), the West Semitic storm-god, whose equivalent in the Greek pantheon is Zeus.[8]

I agree with Doug to a point. The “bull” prefix fits perfectly the context of Mount Hermon as a pagan holy site. However, the connection is not with Baal/Zeus, but with the entity that we’re investigating, El. His chief epithet, “Bull El,” was so well known to the Hebrew prophets that we should read it in at least one, and possibly two, passages in the Bible—Hosea 8:6, certainly (“For who is Bull El?”), and Deuteronomy 32:8 (“the number of the sons of Bull El”) a reasonable possibility.

So, what do we make of batiou? According to Hamp, the word is missing from lexicons, dictionaries, encyclopedias, scholarly sites, and journals. He concludes, “batiou simply is not Greek.”[9]

He does, however, propose an elegant solution. It’s too long to reproduce here, which would not do Doug justice. I refer you to his book Corrupting the Image 2: Hybrids, Hades, and the Mount Hermon Connection for details. In my opinion, Doug’s detective work on the Mount Hermon inscription has drawn the first new information out of this artifact in more than a hundred years.

The summary is this: The Sumerian logogram BAD (or BAT), depicted as two inward-pointing horizontal wedges, designated both Dagan and Enlil. The –iou suffix, Hamp argues, makes the transliterated logogram “standard Greek.”[10] Thus, Hamp’s new translation reads:

“According to the command of the great bull-god Batios [Dagan/Enlil], those swearing an oath in this place go forth.”[11]

I agree, but with a small emendation:

“According to the command of the great Bull El, those swearing an oath in this place go forth.”

Since we’ve established that the names Dagan, Enlil, and El all refer to the same entity, my suggested change really does not constitute a disagreement with Doug’s research.

His translation generally agrees with those of Nickelsburg and Clermont-Ganneau. The important new connection Doug makes is identifying the Sumerian logogram BAD/BAT, which connects Dagan and Enlil to Mount Hermon, and thus to the Canaanite creator-god El and the Watcher chief Shemihazah. Recognizing the bo- prefix (“bull”) strengthens the identification of Dagan/Enlil as “Bull El.” (It’s also more evidence confirming this god’s identity as Kronos, king of the Titans, but we’ll deal with that in an upcoming chapter.) All in all, this is profound.

Amar Annus, whose work is referenced throughout this book, was consulted by Hamp on this new translation of the stela. Annus, in his book on the Akkadian god Ninurta, confirms the link between Dagan, Enlil, and mountains:

The name of Dagan is written logographically dKUR in Emar [an ancient city near the bend in the Euphrates in northern Syria] as an alternative to the syllabic dDa-gan. d KUR is a shortened form of Enlil’s epithet KUR.GAL “great mountain,” which was borrowed by Dagan, and he is already described as the great mountain in a Mari letter. That in Emar there existed a cult for Dagan as dKUR.GAL points to the awareness of Sumerian traditions concerning Enlil, it “shows that some connection with the ancient title was preserved behind the common writing of the divine name as dKUR,” and leaves no doubt that Enlil is the model behind Dagan in Emar.[12] (Emphasis added)

Given that the evidence shows that Enlil was imported to Sumer from the north or northwest, and that Mount Hermon was recognized as a sacred mountain in Babylonia as early as the time of the patriarch Jacob,[13] it’s possible that the “Great Mountain” epithet, applied to Enlil and Dagan, may be attributed to the god’s connection to Mount Hermon.

And the double meaning of the Sumerian word kur (“mountain”/“netherworld”) is likewise appropriate in the context of Hermon and its “double deeps.”

This is reinforced by a text dated to the time of Israel’s sojourn in Egypt, probably the seventeenth century BC, that mentions a king of Terqa offering “the sacrifice of Dagan ša ḪAR-ri.”[14] Scholar Lluis Feliu compares this with a later text from Emar that mentions a “dKUR EN ḫa-ar-ri that we may translate as ‘Dagan, lord of the hole/pit’.”[15] Then Feliu untangles the meaning of ḫa-ar-ri and reaches an interesting conclusion:

A different question is the interpretation…of the term ḫa-ar-ri. The vocalisation in a suggests identifying this word with Akkadian ḫ arrum “water channel, irrigation ditch.” However, the semantic and morphological similarity with ḫurrum “hole” makes it possible to understand the epithet, tentatively, as “The Dagan of the pit.” This interpretation could find confirmation in the following line in the text Emar 6/3 384, where, after [dKU]R EN ḫa-[ar-ri], there occurs dINANNA a-bi. [Note: Inanna is the Sumerian goddess of sex and war, better known as Ishtar.]

As yet, the term a-bi has not been given a satisfactory translation and its meaning is much discussed. One of the interpretations that has been proposed is “pit,” based on Hurrian a-bi. [16] (Emphasis added)

You probably recognize the link to the abi, the ritual pit of Kumarbi at ancient Urkesh and the pagan worship of the underworld spirits and gods it inspired. The ancient Amorite texts cited by Feliu connect Dagan to these necromantic practices and strengthen our theory that Dagan, Kumarbi, Enlil, El, and Assur are one and the same.

We’ve covered a lot of ground in this section, but another important piece of evidence links this entity, as Dagan, to the Bible. It also comes from Emar, the city that’s provided us with solid evidence to identify Dagan as Enlil, and it’s reflected in the most important annual feast given by God to the Hebrews.

The pagan religious calendar in the ancient Near East featured a festival called the akitu that dates back at least to the middle of the third millennium BC.[17] It was thought to be a new year festival held in the spring to honor the chief god of Babylon, Marduk, but more recent discoveries have shown that there were two akitu festivals, one in the spring, the harvesting season, and the other in the fall, the planting season, and some of them were performed to honor other gods. For example, the oldest known akitu is documented at ancient Ur in Sumer, which was the home city of the moon-god, Sîn.[18]

The akitu festivals began on the 1st of Nisan and 1st of Tishrei, close to the spring and fall equinoxes. Although the length of the festivals changed over the years, it appears they generally lasted eleven[19] or twelve days.[20] So, the Jewish festivals began a few days after their pagan neighbors finished their harvesting and planting rituals.

Sukkot is a seven-day festival. It’s particularly interesting because of the sheer number of sacrificial animals required, especially because they were bulls. Numbers 29:12–34 spells out the requirements for the Feast of Booths.

| DAY 1 | DAY 2 | DAY 3 | DAY 4 | DAY 5 | DAY 6 | DAY 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 bulls | 12 bulls | 11 bulls | 10 bulls | 9 bulls | 8 bulls | 7 bulls |

| 2 rams | 2 rams | 2 rams | 2 rams | 2 rams | 2 rams | 2 rams |

| 14 lambs | 14 lambs | 14 lambs | 14 lambs | 14 lambs | 14 lambs | 14 lambs |

| 1 goat | 1 goat | 1 goat | 1 goat | 1 goat | 1 goat | 1 goat |

The Feast of Unleavened Bread, which was likewise a seven-day festival, required only one ram and seven lambs each day. But the biggest difference between the two feasts is that only two bulls were sacrificed each day during the Feast of Unleavened Bread.[21] In fact, none of the other festivals ordained by God for Israel required the sacrifice of more than two bulls per day.

This suggests that Sukkot was unique in the annual calendar. In fact, in several places in the Old Testament it’s simply called “the festival” or “the feast.”[22] But why so many bulls at this particular feast? And why the decreasing number of bulls slaughtered each day?

We may never know specifically, but it’s fascinating (and not coincidental, in my view) that Sukkot bears an interesting resemblance to a festival called the zukru attested during the time of the judges at Emar:

On the month of SAG.MU (meaning: the head of the year), on the fourteenth day, they offer seventy pure lambs provided by the king…for all the seventy gods [of the city of] Emar.[23]

Seventy lambs for the seventy gods of Emar, headed up by Dagan, sacrificed over seven days during a festival that began in the first month “when the moon is full,” just like at Sukkot.

Pop quiz: How many bulls were sacrificed at Sukkot? 13 + 12 + 11 + 10 + 9 + 8 + 7 = 70.

Dagan’s underworld connection as the bē l pagrê, “lord of the corpse” or “lord of the dead,” links this identity to El, Baal-Hermon, lord of the mountain that towers over Bashan, which was believed to be the entrance to the netherworld. Dagan was worshiped as the father of “seventy gods”—i.e., “the complete set,” or “all of them,” in the same way that El held court on Mount Hermon with his consort, Asherah, and their seventy sons.[24]

Was this a coincidence? Dr. Noga Ayali-Darshan of Israel’s Bar Ilan University thinks not:

In light of the Emarite custom, I would like to propose that the law in Numbers 29 prescribing the offering of seventy bulls during Sukkot—which has no parallel in any other Israelite festival—reflects the old Syrian custom of offering seventy sacrifices to the seventy gods (i.e., the whole pantheon) at the grand festival celebrated in the month of the New Year.[25]

I would go further: In light of the seventy “sons of God” allotted to the nations after the Tower of Babel incident, which matches the number of names in Genesis 10’s Table of Nations, God’s requirement of seventy sacrificial bulls during Sukkot was a deliberate message to the Israelites, a reminder that He’d delivered them from the gods of the nations.

It was also a clear message to rebellious elohim, both the Watchers who’d descended to Mount Hermon and the group placed over the nations after Babel: This is what’s in store for you.

Next: The loathsome dead god