The Second Coming of Saturn Part 28: The Return of Saturn’s Reign

During the transition from the Roman Republic to the Roman Empire in the first century BC, the Roman poet Virgil invoked the Golden Age of Saturn to recall the “good old days” when life was easier, people were nobler, and everyone was happy. Virgil used that imagery in his poetry to suggest that Julius Caesar’s nephew, Octavian, who emerged from a power struggle with Mark Antony to become Caesar Augustus, would usher in a return to that blessed time.

But the language Virgil used should cause you, as an alert reader, to sit up and take notice:

Now the last age by Cumae’s Sibyl sung

Has come and gone, and the majestic roll

Of circling centuries begins anew:

Justice returns, returns old Saturn’ s reign,

With a new breed of men sent down from heaven.

Only do thou, at the boy’s birth in whom

The iron shall cease, the golden race arise,

Befriend him, chaste Lucina; ’tis thine own

Apollo reigns. And in thy consulate,

This glorious age, O Pollio, shall begin,

And the months enter on their mighty march.

Under thy guidance, whatso tracks remain

Of our old wickedness, once done away,

Shall free the earth from never-ceasing fear.

He shall receive the life of gods, and see

Heroes with gods commingling, and himself

Be seen of them, and with his father’s worth

Reign o’er a world at peace.

[…]

Assume thy greatness, for the time draws nigh,

Dear child of gods, great progeny of Jove! (Emphasis added)[1]

The Roman poet Virgil

Virgil’s Eclogue IV undoubtedly served a political purpose. Artists and poets need patrons to pay their bills, and the Pollio named in Virgil’s poem was Gaius Asinius Pollio, a politician, orator, poet, playwright, literary critic, historian, and soldier. In 40 BC, Pollio began a term as consul, the highest elected official in Rome after helping arrange the Treaty of Brundisium. The pact cooled a growing rivalry between Octavian and Antony, two of the three members of the Second Triumvirate, the men who held the real power of the Roman state. On the surface, Virgil’s poem was propaganda for the incoming administration, hailing a new age of peace and prosperity after decades of turmoil and civil war that peaked with the rise and fall of Julius Caesar.

On a deeper level, however, Virgil’s poem refers to a lost prophecy from the oracle of Apollo at Cumae, a Greek colony near Naples, of a return to an age that ended when Jupiter dethroned Saturn—or, in biblical terms, when God sent the Flood. The new Golden Age would be ushered in by a messianic figure, a child who would become divine and rule over a world at peace.

But the earth had lived through that story once before and suffered intensely under the “new breed of men sent down from heaven” before the deluge. They were the mighty men of old called “Nephilim” in the Hebrew Scriptures, and “Rephaim” by the ancient Hebrews and their neighbors—demigods, semi-divine heroes, venerated in the religions of Greece and Rome.

To those familiar with the Genesis 6 backstory, the influence of the Watchers/Titans and Nephilim/“heroes” on later Greek and Roman religion and the role of the dark god Saturn/Shemihazah in leading the Watchers’ rebellion, Virgil’s poem is startling. Did pagans of the classical era really look back on the pre-Flood world with longing and nostalgia? Apparently so. And this desire to return to the Golden Age is still alive today.

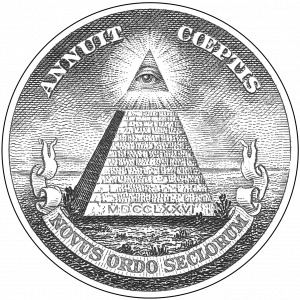

Eclogue IV is the source of a phrase you’re probably carrying in your wallet or purse right now. Charles Thomson, secretary of the Continental Congress from 1774 to 1789, designer of the Great Seal of the United States, placed the Latin phrase novus ordo seclorum (“new order of the ages”) below the unfinished pyramid on the reverse side of the seal. That’s a loose adaptation of line 5 of Virgil’s poem: Magnus ab integro seclorum nascitur ordo (“the majestic roll of circling centuries begins anew”).[2]

Thomson adapted the other Latin phrase on the reverse of the seal from Virgil, too. Annuit cœptus, taken from The Georgics Book I, line 40, essentially means, “Providence favors our undertakings.”[3] The question, of course, is who was meant by “Providence.” I don’t know Thomson’s heart, so it’s possible he meant the God of the Bible. The other, more important, question is what meaning others ascribe to that symbol. Although Freemasons deny that the Eye of Providence is one of their symbols, and there is no evidence that Thomson was a Freemason, the All-Seeing Eye was recognized as a masonic symbol in 1797,[4] some fifteen years after the Great Seal was adopted—although the two eyes “are parallel uses of a shared icon.”[5]

Tom Horn dissected the occult symbolism of the Great Seal in Zeitgeist 2025 and Zenith 2016, so I’ll direct you there for a thorough examination of its hidden meaning. The reverse side, the more relevant of the two, gained new importance when it was added to the back of the dollar bill in 1935. This was initiated by Vice President Henry Wallace, 32nd-Degree Scottish Rite Freemason, whose fellow 32nd-Degree Mason, President Franklin Roosevelt, directed that the reverse side of the Great Seal be added to the left back of the dollar and the obverse side be placed on the right, creating the impression that the mysterious pyramid and Eye of Providence were the principal symbols of the United States.[6]

Tom Horn dissected the occult symbolism of the Great Seal in Zeitgeist 2025 and Zenith 2016, so I’ll direct you there for a thorough examination of its hidden meaning. The reverse side, the more relevant of the two, gained new importance when it was added to the back of the dollar bill in 1935. This was initiated by Vice President Henry Wallace, 32nd-Degree Scottish Rite Freemason, whose fellow 32nd-Degree Mason, President Franklin Roosevelt, directed that the reverse side of the Great Seal be added to the left back of the dollar and the obverse side be placed on the right, creating the impression that the mysterious pyramid and Eye of Providence were the principal symbols of the United States.[6]

As Tom wrote in Zenith 2016, their meaning was clear to Wallace and other adepts:

Wallace viewed the unfinished pyramid with the all-seeing eye hovering above it on the Great Seal as a prophecy about the dawn of a new world with America at its head. Whenever the United States assumed its position as the new capital of the world, Wallace wrote, the Grand Architect would return and metaphorically the all-seeing eye would be fitted atop the Great Seal pyramid as the finished “apex stone.” For that to happen, Wallace penned in 1934, “It will take a more definite recognition of the Grand Architect of the Universe before the apex stone [capstone of the pyramid] is finally fitted into place and this nation in the full strength of its power is in position to assume leadership among the nations in inaugurating ‘the New Order of the Ages.’”[7]

While it’s understandable that a New Ager like Henry Wallace would look to Virgil’s poetry and the symbolism it inspired as prophecy to be fulfilled, even Christians began interpreting Virgil’s fourth Eclogue as prophecy in the early fourth century, seeing in it a foretelling of the imminent birth of Christ.[8] Lactantius, an early Christian writer and religious advisor to the Roman emperor Constantine, may be the one who first proposed this reading of the poem.[9] In his Divinae Institutiones (The Divine Institutes), Lactantius described Virgil’s poem as a prophecy of the return of Jesus prior to His millennial reign.[10] About a century later, Augustine of Hippo argued that it was apparent that Virgil had repeated an authentic prophecy uttered by the Cumaean Sibyl.[11] This belief was widespread as late as medieval times, with many scholars across the centuries convinced that Virgil was a legitimate pre-Christian prophet.

It appears that his reputation carried over from the pagan world. The writings of Virgil were used as oracles in a practice called the Sortes Vergilianae (“Virgilian Lots”). That was a form of divination by interpreting passages selected at random from the works of the poet, in the same way that some Christians read meaning into Scriptures selected by opening the Bible and reading the first verses that come to hand. It’s known that at least four Roman emperors (and at least one usurper) tried to divine the future through the poetry of Virgil. Even as late as the seventeenth century, England’s King Charles I, at the suggestion of the poet Abraham Cowley, consulted the Aeneid in December of 1648 while he was held captive by forces loyal to Oliver Cromwell.[12] The verses Charles chose did not bode well, and sure enough, the deposed king was dead within a year.