The Second Coming of Saturn Part 3: Secrets and Spirits

December 5, 2021 by Derek Gilbert

by Derek Gilbert

The story in the Book of 1 Enoch would make a compelling supernatural thriller. It has two main villains—Watcher-class angels named Shemihazah and Asael (sometimes rendered Azazel).

Shemihazah, as noted in the previous section, is the leader of the rebel faction—their king, if you will. Afraid that he’d be left holding the bag, he convinced the rest of the two hundred who followed him to Mount Hermon to swear and bind one another with an oath and a curse. Chapters 6 and 7 of 1 Enoch focus on Shemihazah and the mixing of human and angelic bloodlines.

The sins of Asael form another narrative that’s worth our attention. While Shemihazah is called the chief of the rebellious Watchers, chapter 8 of 1 Enoch blames Asael for myriad sins:

Asael taught men to make swords of iron and weapons and shields and breastplates and every instrument of war. He showed them metals of the earth and how they should work gold to fashion it suitably, and concerning silver, to fashion it for bracelets and ornaments for women. And he showed them concerning antimony and eye paint and all manner of precious stones and dyes. And the sons of men made them for themselves and for their daughters, and they transgressed and led the holy ones astray. And there was much godlessness on the earth, and they made their ways desolate….

You see what Asael has done, who has taught all iniquity on the earth, and has revealed the eternal mysteries that are in heaven, …

[A]ll the earth was made desolate by the deeds of the teaching of Asael, and over him write all the sins. (1 Enoch 8:1; 9:6; 10:8, Hermeneia Translation)

In a nutshell, Shemihazah was blamed for the cohabitation of angels and women while Asael was responsible for teaching humans forbidden knowledge. Unlike the Shemihazah story, the role of Asael role in 1 Enoch has no parallel in Genesis 6, which only deals with the creation of the Nephilim. Likewise, Peter and Jude only mention the sexual aspect of the Watchers’ sins. However, this transfer of secrets from the divine realm to humanity influenced Jewish religious thought in the pre-Christian era.

Since 1999, Amar Annus has produced invaluable work showing the links between Jewish theology and the religions of their Mesopotamian forebears and the later Greeks and Romans. Added to earlier landmark works such as Martin L. West’s 1997 book The East Face of Helicon and Michael C. Astour’s Hellenosemitica, published in 1965, it is now clear that the origins of the so-called myths of classical Greece and Rome can be traced back through the Semitic people of the Levant to ancient Babylon, Akkad, and Sumer.

The research of Annus and others has revealed that the Watchers of Hebrew theology were known in ancient Mesopotamia by the Akkadian name apkallu (Sumerian abgal), which roughly translates as “big water man.”[1] This refers to their home, which was believed to be the freshwater ocean beneath the earth, the Aps û or abzu, from which we get the English word “abyss.” This was the domain of Enki, the clever god who alone among the Sumerian deities was always favorably disposed toward humanity. (The others you could never be sure about.) The apkallu were divine sages, on the earth before a great flood swept over the land of Sumer, who brought the gifts of civilization from Enki to humanity.

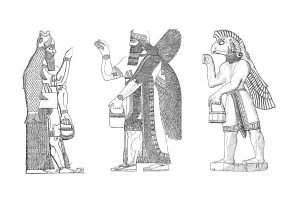

The three forms of apkallu in Mesopotamia (click to enlarge) [2]

There were three types of apkallu: A bearded man with wings, a hawk-headed humanoid with wings, and a man who appeared to wear a fish cloak. The fish-garbed apkallu has been incorrectly identified as the god Dagon or one of his priests, thanks to Alexander Hislop’s 1858 book The Two Babylons. Hislop meant well, but he was mistaken. As we’ll see later, Dagon (originally spelled “Dagan”) was a grain-god, not a fish-god.

While the apkallu were believed to be the source of all Mesopotamian priestly knowledge, they were also connected to sorcery and were occasionally considered dangerous, demonic beings. They were invoked as protective spirits in Mesopotamia, but were viewed as the origin of evil by the later Hebrews. Interestingly, the Babylonian Epic of Erra records that the apkallu had been banished forever to the Aps û by the chief god Marduk as a consequence of the great flood, just as the sinning angels had been thrust down to Tartarus by God.[3]

The Apostle Paul wrote to the church at Rome that “sin came into the world through one man,”[4] that being Adam. That is true, but unlike Christians, who blame the fallen state of the world on Adam’s sin, Jews in Jesus’ day also pointed to the incidents of Genesis 6 and 11, the Mount Hermon rebellion and the Tower of Babel. I’ve gone into detail on the consequences of Babel elsewhere, especially chapter 3 of my book The Great Inception, so I won’t repeat that here. To summarize: Babel was humanity’s attempt to build an artificial mountain as an abode for the gods. I believe this was the ancient temple at Eridu, the ancient cult center of Enki. Nimrod tried to build this divine abode right on top of the Aps û, the “abyss.” As punishment, God delegated supervision of the earth to another group of “sons of God.”[5] They rebelled, too, and so God decreed their deaths. You’ll find that in Psalm 82, which reads like a courtroom scene in heaven:

God has taken his place in the divine council;

in the midst of the gods he holds judgment:

“How long will you judge unjustly

and show partiality to the wicked? Selah […]I said, “You are gods,

sons of the Most High, all of you;

nevertheless, like men you shall die,

and fall like any prince.” (Psalm 82:1–2, 6–7)

Those “sons of the Most High” are the pagan gods of the neighbors of the ancient Israelites—from Baal, Asherah, Astarte, and Chemosh to Zeus, Apollo, Artemis, and Ares.

The entities we’re concerned with belonged to an earlier age. These were the deities later called the “old gods” or “former gods” by the pagans. The Hebrews referred to them as Watchers. The Mesopotamians called them apkallu, although there is another tradition in the religion of Sumer, Akkad, and Babylon that the gods who formerly ruled the heavens, the Anunnaki, had become judges of the underworld by the time of the Old Testament patriarchs.

The Old Babylonian copy of the Epic of Gilgamesh connects the mountain of the Watchers’ oath to the old gods of Sumer, describing the cedar forest around Mount Hermon as the “secret dwelling of the Anunnaki.”[6] Hermon overlooks the land of Bashan, which was considered the literal entrance to the netherworld by the Canaanite neighbors of ancient Israel. The tale of Gilgamesh thus links the rebellion of the Watchers to the old Sumerian gods who, at some point in history, were demoted from the heavens to the underworld—like the Titans of the Greeks.

Since Shemihazah was the chief of the group that descended to Hermon, it’s a good guess that he can be identified as Kronos, the youngest of the twelve Titans believed to have been born to Gaia by the sky-god, Ouranos. (We can assume that stories of gods born to older gods were created for human consumption by the rebel angels. According to Jesus, angels in heaven “neither marry nor are given in marriage,”[7] probably because eternal spirit beings don’t need to procreate.) Asael was singled out for the sin of revealing hidden knowledge to humanity. The character in Greek myth that most fits his story is the Titan Prometheus, who was sentenced to eternal torture in Tartarus by Zeus for stealing fire from Olympus and giving it to humanity. For his crime, Prometheus was chained to a rock, helpless, while an eagle ate his liver. Every night, the liver grew back, so the gruesome process would repeat the following day, and the day after that, ad infinitum.

Chapter 10 of 1 Enoch describes how Asael, who was obviously more deserving of punishment than Prometheus, was bound by the archangel Raphael, dropped into a hole in the desert onto jagged rocks, and covered with darkness where he will remain until Judgment Day. This is strikingly similar to Peter and Jude’s description of the sentence meted out to the angels who sinned.

The punishment of Shemihazah was assigned to Michael, who was commanded to bind him and the other Watchers who had “defiled” themselves with women for seventy generations in the “valleys of the earth.”[8] Note that “seventy” in the ancient Near East was not a literal number, but a symbol that represented “all of them.” In other words, Shemihazah and his colleagues are imprisoned in the netherworld until the end of the age, the time of the final Judgment.

We’ll go into more discussion of the parallels between the Watchers of Enoch and the Titans of Greece in a future article. The other important consequence of the sin of the Watchers that we need to discuss here is the creation of demons.

It is explicit in 1 Enoch that the giants after death became “evil spirits,” condemned to wander the earth until the Judgment. The mixing of human and divine was forbidden, so the spiritual part of the giants were to remain on earth, suffering hunger and thirst but unable to satisfy those wants, afflicting and oppressing humankind until the great Judgment.[9] This is the textbook definition of a demon.

The oldest sections of the Book of 1 Enoch, which includes the Book of the Watchers, were probably written no earlier than the Greek period of Israel’s history, after Alexander the Great conquered the Levant in the late fourth century BC. This means that the Hebrew Scriptures of the Tanakh, the Christian Old Testament, are older than 1 Enoch. And there are very few references to demons in the Old Testament; in fact, the word “demon” is only used three times. In Leviticus 17:7, Hebrew se’irim is rendered “goat demon,” which is especially interesting in this context. Leviticus 16 records the instructions given by God to Moses and Aaron for the Day of Atonement, during which they were to cast lots over two male goats. One was sacrificed as a sin offering to God, but Aaron was to take the other, place his hands on its head and transfer the sins of Israel onto the goat, then send it “into the wilderness for Azazel.”[10] This wasn’t an offering to Azazel/Asael; the goat carried the sins of the people out of the camp, which was ground sacred to Yahweh, and into the wilderness, which was Asael’s jurisdiction.

This is consistent with other Jewish writings from the Second Temple period that depict the desert wilderness as a place occupied by demons. This gives a different flavor to the verse from Isaiah quoted by John the Baptist: “A voice cries: ‘In the wilderness prepare the way of the Lord; make straight in the desert a highway for our God.’”[11] The herald boldly calling for God’s people to prepare for His arrival was in enemy territory!

In Deuteronomy 32:17 and Psalm 106:37, “demon” is used for the Hebrew word shedim. This is probably based on the Akkadian shadu, which means “mountain” and may be the word behind El Shaddai (“God of the Mountain”). The Akkadian shadu were protective spirits also called lamassu. They were typically depicted as winged creatures with the bodies of lions or bulls and human faces. The famous lamassu at the British Museum, which once stood guard outside the palace of the Assyrian kings at Nineveh, are winged, human-headed bulls with the feet of lions.

Derek Gilbert with an Assyrian lamassu at the British Museum

Note that the lamassu possesses the four aspects of the biblical cherubim—human (face), lion (paws), ox (body), and eagle (wings). This is not a coincidence. The shedim, then, were lesser supernatural beings, possibly fallen cherubim, who were venerated by the pagans.

However, there is nothing at all in the Old Testament about the differences between fallen elohim, like the “sons of God” in Genesis 6 and Psalm 82, and the demonic spirits described in 1 Enoch. You won’t find anything about the origins of demons, either. That doctrine comes into focus sometime around 300 BC with the Book of 1 Enoch.

We could ignore what Enoch has to say about demons if the section of 1 Enoch we’re discussing, the chapters called the Book of the Watchers, hadn’t been referenced by Peter and Jude. But it’s clear that their knowledge of the transgressing angels, especially their punishment, came from 1 Enoch. So, while most of the Christian church doesn’t consider it inspired Scripture, 1 Enoch is useful insofar as it helps us understand Genesis 6 and the sin of the angels mentioned by Peter and Jude.

The early church clearly accepted the origin story of demons that’s straight out of chapters 7 and 15 of 1 Enoch. Christian theologians for the first four hundred years after the Resurrection were almost universally agreed that demons are the spirits of the Nephilim destroyed in the Flood, and that the Nephilim were the children born from the infernal unions of rebellious Watchers and human women.

That is the legacy of Shemihazah, chief of the Watchers who descended to Mount Hermon in the distant past. By leading his two hundred colleagues to violate the species barrier and produce children with human wives, he set in motion a chain of events that continues to impact the world to this day. Shemihazah essentially created a supernatural army—one that deceived Israel into offering sacrifices to the dead before Joshua led the people into Canaan.