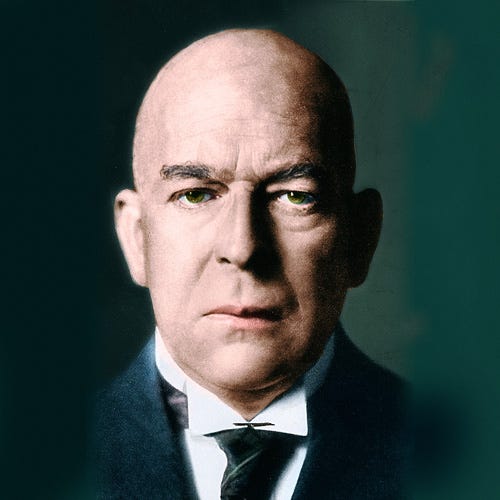

Lately, I have been grappling with a persistent depression. It began after I read Oswald Spengler’s Decline of the West —a demanding work that required me to learn its unique lexicon and concepts. The true weight settled in not during the reading, but after, when I began, almost involuntarily, to view the world through a Spenglarian lens.

To understand why, it’s essential to see that Spengler’s work transcends conventional history. He is not concerned with cataloguing dates, battles, or biographies. Instead, he constructs a grand Philosophy of History by discerning the organic life cycles of civilizations—their birth, growth, maturity, and inevitable decline. This approach shifts the focus from chronicled events to the underlying morphology of cultures, treating them as living organisms with a destined lifespan.

Make no mistake: in doing so, Spengler created a powerful and provocative model—one that compels us to view the rise and fall of societies not as accidents, but as the expression of deep, inescapable cultural destinies. The true source of its somber power, however, lies in his core principle of the cosmic bond between a people and its landscape. For Spengler, a Culture is not an abstract idea; it is a primeval force, a “Cosmic Plant,” that awakens in the deep, unconscious unity of a people and its terrain. From this primal, almost mystical symbiosis, everything unique to that civilization emerges: its art, its architecture, its mathematics, its very conception of the world. The Maya, gazing from their limestone pyramids into the vault of the Venus cycle, and the Inca, engineering a vertical empire in the impossible geometry of the Andes, were not merely “advanced societies.” They were the sublime and necessary expressions of a people and a place become one—the ultimate manifestation of a Destiny that, once fulfilled, cannot be repeated.

And it is precisely this fatalistic morphology that has cast its long shadow over my mind. For if a civilization’s highest form is inextricably bound to this primal unity, then its decay is not merely a historical event, but an organic fatality. Seeing the patterns he describes—the transition from vibrant Culture to sterile Civilization—play out in the present can feel less like understanding history and more like witnessing a twilight, knowing that what was once born in symbiosis must eventually return to dust.

The Spenglerian cultural organism does not merely inhabit its environment—it is a morphological expression of it. In the Andean region, where temperate highlands, humid rain forests, and arid coastal zones exist in radical vertical proximity, the civilization that emerged required an exact, coordinated reading of seasonal micro-climates. Economic stability and social continuity depended on this precise harmony. Indeed, the cultural organisms of Central and South America formed under conditions defined by an intimate, necessary symbiosis between distinct biogeographic realities and the peoples adapted to them. It was this deep-rooted bond—this fated unity of people and place —that gave rise to complex cultures and enforced their preservation through tradition.

This relationship is encoded in their very conception of reality. The cyclical time of Indigenous American societies expresses how these populations linked social and cosmic order to the repetition of the ecological phenomena that conditioned their existence. The formation of their historical space follows the same organic logic. In Mesoamerica, urban centers were not placed arbitrarily; they were strategically situated in valleys and basins where access to water, soil fertility, and control over exchange routes facilitated the continuity of the population—the preservation of the cultural organism itself. Pyramids and ritual complexes are, therefore, not mere ceremonial sites. They are points of sacred articulation between agricultural life, celestial order, and political cohesion. Their location and orientation reflect a society that integrated astronomy, hydraulics, and urban planning into a single, territorially-adapted scheme.

For Spengler, space is never an empty vessel for aimless expansion. It is a destined landscape, a structured element of the Culture’s soul. Every core settlement had to ensure a ritual and practical balance between production, water, and demographic stability—what translates, in Spenglerian terms, as the preservation of the people within its Soil. While the expressions differed between the Andes and Mesoamerica—the geography demanded different efforts—this same principle held. It was this very morphological bond between territory, time, and social structure that enabled these cultural organisms to achieve profound complexity endogenously, without need for external models. They required no Europeans, no friars. Their form was their own destiny.

Consequently, their vital impulse—what Spengler would call their prime symbol —differed fundamentally from the Faustian soul of the West. Indigenous cultures did not seek limitless spatial expansion, that Faustian “yearning for the infinite.” Instead, their energy was directed inward and upward: toward the precise, cyclical regulation of resources and the maintenance of stable equilibrium within a complex ecological and cosmic frame. Their greatness was one of depth, not breadth.

For me, the Maya civilization is the most profound and complete illustration of this process. Their development, spanning millennia across the highlands and lowlands of the Yucatán, represents a full Spenglerian life-cycle in one contained study. A critical question arises: you can visit the region today and see Maya people. But does their presence signify the continuity of the Culture? Spengler would argue it does not. The Civilization phase—the final, inorganic, cosmopolitan state—is terminal. When that cycle concludes, the living Culture-soul does not return. The “Mayanness” of the Classic period is a closed book, a fulfilled destiny. Its monumental cities are not ruins of a past, but the corpse of a completed life.

Studying this cycle is a mirror. Having developed over a comparable span, Faustian (Western) culture finds itself in a analogous, late stage. My point, therefore, is this: language, law, and superficial institutions are not enough to sustain the cohesion of an organic cultural organism once its inner vitality has waned. What Spengler reveals is that at the civilizational level—the level of longue durée morphology—the deeper, pre-intellectual bonds are essential. It is the inextricable, fateful connection between a formative People and its destined Landscape that shapes a Culture’s birth, governs its expression, and marks the hour of its inevitable end.

The Mayan civilization serves as the definitive textbook case for applying Spengler’s Morphology of History. Consider its span: one thousand years—a full millennium. This unparalleled duration allowed for the complete consolidation of its form: the rise of cities, vast trade networks, agricultural systems perfectly adapted to diverse soils, a developed writing system, sophisticated astronomy, and the monumental architecture that defines its urban centers. We are witnessing a profound demographic persistence and a masterful, sustained adaptation to a complex environment.

Yet, by the period immediately preceding European contact, Mayan culture was no longer in a phase of creative expansion. It was in a state of full disintegration. Many of its great cities had been abandoned or repurposed into smaller regional centers. In Spenglerian terms, its cultural organism had exhausted its internal possibilities and was approaching its closure—its final, civilizational winter. This was not a collapse from without, but a completion from within.

In the Maya, we can trace with textbook clarity the full arc of Spengler’s historical morphology:

- The Pre-Cultural Stage: The formative, tribal beginnings in the Preclassic period.

- The Early Culture Phase: The emergence of a distinct spirit and symbolic forms (evident in early art, cosmology, and the first ceremonial centers).

- The Late Culture Phase: The flourishing of intellect and the crystallization of form—the Classic Maya peak of Tikal, Palenque, and Calakmul.

- Civilization: The age of great, soulless concentrations of power and practical materialism, seen in the later northern centers like Chichén Itzá.

- Decline: The irreversible fragmentation where the original creative force is spent, and the forms harden and crumble—the Post-Classic reality.

This morphological completeness in no way diminishes their historical depth. On the contrary, it grants us a privileged lens. The Inca and Mexica civilizations were catastrophically interrupted in their late stages. The Maya alone passed through the entire cycle. This completeness is what makes them the profound comparative mirror for our own Faustian late age.

And this leads to the critical, and tragically overlooked, implication for the present. No one will be able to understand the historical situation of Hispanic America without this morphological understanding. If you are Hispanic American, you are likely a Criollo (Descendant of Spaniards) or Mestizo. You are, in a profound sense, twice removed from yesterday. You are no longer of the Indigenous cultural organism, whose cycle was either completed or severed. Nor are you of the pure, transplanted Hispanic culture of the Conquistador, which itself was a late-Civilization expression of a fading Spanish culture .

Your identity was forged in the aftermath, in the crucible of civil wars and the Masonic liberal project—a project that is, in a deep sense, an absolute failure. For what Freemasonry and its Enlightenment derivatives effectively achieved was the systematic erasure of those primal, morphological connections. It replaced the sacred bond between a People and its Landscape with abstract universals and contractual citizenship.

Thus, we find ourselves in a position more precarious, more spiritually dislocated, than the Maya, Inca, or Mexica at their end. They possessed, at least, the integrity of their own completed form—the fatal unity of their blood and soil. Our identity does not. We inhabit a historical void between two completed cycles, shaped by an imported ideal that is neither Indigenous nor authentically Hispanic, but deracinated and abstract. You may think otherwise, but trace the lineage of the republics, the symbols, the founding doctrines: they are linked to the Masonic ideal. An ideal that is not Maya, not Inca, not Mexica, not truly Hispanic. It is the ghost of a Faustian Civilization, building its monuments on ground it cannot truly fathom. In my humble opinion, this is the tragic root of the confusion.

The European presence meant for the indigenous peoples one thing: a total morphological overhaul. It was not an adaptation, but a reorganization of space, a swap of political soul, and a demographic reconfiguration. This was no natural continuation for Mesoamerican or Andean cultures; it was the catastrophic imposition of an alien system—a complete package of practices, techniques, and power structures answering to a history and a destiny entirely separate from their own.

We are confronting the abrupt arrival of a foreign culture in its expansive, Civilization phase. Its practices, political orders, and beliefs sprang from a unique historical moment—the Castile of the late 1400s, driven outward by the Faustian prime symbol: the yearning for infinite space. Its true Heimat, its spiritual home, was Europe. That is where its soul was forged, its people formed, and its ancestors buried—not in the Americas. This was an external force, projecting its own unresolved destiny onto alien soil.

As Spengler makes clear, a true cultural organism requires more than a common language; it demands a shared, defining historical landscape, a destined space. The worlds of the Mediterranean and the Atlantic operated on a historical and ecological logic completely separate from that of the Americas. Consequently, the Spanish identity—forged by a people and tied irrevocably to European soil—was, at that moment, fundamentally disconnected from the American reality. Their presence meant a radical reorganization that shattered the existing balance achieved by cultures of the highest complexity. To state it morphologically: they broke a living form and imposed their own.

A new state-model was imposed, one that interrupted the autonomous development of cultural organisms that had already achieved their own internal structure and maturity. The Spanish possessed a capacity the native peoples, by their own organic development, lacked: the Faustian drive and technical ability to articulate vast territories through abstract, stable governing structures. There was no experience in the Americas equivalent to Rome—a continent-spanning imperial framework of administration and law. This organizational and political-technical gap was decisive. The Castilians possessed a far greater capability—one rooted in their Faustian will to impose their nomos upon any land. They were the ones who named this new world, gave it a bureaucratic and spiritual form, and enforced that reality. To this day, the geopolitical world still lives within the frameworks established by that expansive, infinite-seeking European soul.

If you go to South or Central America, you’ll find the descendants of the Maya, the Aztec, the Inca. And they understand this history intuitively—they are not confused by Masonic abstractions. The real tragedy, in their telling, is not the so-called discovery, or even the conquest per se. The real tragedy is what happened to the internal machinery of their worlds—the advanced social and technical structures they had built, which were broken and replaced.

The critical, and often silenced, point is this: if you speak with these communities and listen carefully, they will state unequivocally that the actions of the Catholic Monarchy were far less destructive to their continuity than those of the Criollo and Mestizo elites who followed. The Libertadores and their Masonic republics systematically sought to erase indigenous identity, replacing it with a fabricated, abstract national one. This was a profound reversal. The Spanish Monarchical system, had at least recognized the ‘Indian’ as a distinct legal and political entity—a pillar, however within a structure. The republics dismantled this framework entirely in the name of a universal citizenship that was, in practice, a mandate for assimilation and cultural erasure.

Let us be clear: for the enduring spirit of the Maya, the Inca, the Aztec, the Tlaxcaltec—the deeper object of blame the Criollo and the Mestizo. Not the Spaniard. This is not to absolve the Conquest, but to recognize a more profound betrayal. The Spanish, however violently, ultimately incorporated the existing Indigenous world into a new, syncretic structure. They built a New Spain with them. There are 154 World Heritage Sites all of them build by the Indians with their Padres.

What the “Libertadores” and their imported Enlightenment ideology effectively did, was not to build upon what was there; they sought to erase its very foundations. They destroyed the legal and social compacts that had preserved a space for the indigenous world, rejecting its continuity in favor of a clean slate. In doing so, they chose an identity that is none of these: not Inca, not Maya, not Aztec, not authentically Hispanic, and not truly Catholic. They chose an abstract, borrowed future—the deracinated ideal of the Masonic lodge—over a complex, living past. Leaving a people twice removed: from the indigenous cultural organism that was severed, and from the Hispanic form that was rejected. Orphans of two completed cycles, building a state on a soil whose deeper history the founding myths of those states actively deny.

This is not about prejudices or claims of inferiority. It is about morphology. The rupture of 1492 shattered the living cultural organisms of the Americas, and that rupture never, never led to the re-emergence of a new, unified cultural organism with its own internal logic and destiny.

There is no alignment—no true coincidence—between the parts that should constitute a coherent whole. This is why we have countries with deficient state apparatuses, institutions that mimic European forms (in education, law, health) but lack their foundational reality. They are imitations, and critically, they lack the deep-rooted, native developmental strata from which those forms originally grew. There were no universities here; the Spanish introduced them. No republics; the Criollos imported them.

Lacking the true internal unity of a living cultural organism, there is no possibility for a different outcome. Not now, not ever.

Instead, heterogeneous societies formed—indigenous groups, Europeans, and mestizo sectors existing side-by-side with distinct traditions, agricultural practices, and legal frameworks. Neither the Spanish imperial system nor the later Masonic liberal-progressive state were born of this soil. They are, and remain, potted plants.

This is the lived reality. This is the “homeland” people possess. They shout 19th-century independence slogans and don European military costumes for parades—traditions that are pure imports, with no morphological connection to the American landscape. If they were truly reclaiming a Native American past, they would dress and act according to those modes. But they do not. They cannot. They are neither one thing nor the other, inhabiting a borrowed shell—a political and cultural form that never took organic root.

The people who understand this are, tellingly, the native communities of Central and South America, and certain sectors of the Hispanista Criollo minority. They grasp the primal connection to the land and the tragedy of its severance. The vast majority of Criollos and Mestizos, however, are lost in a Masonic sea of abstract universalism, possessing no identity anchored in a living cultural destiny. However hard it sounds, that is our reality and our future.

Consider the entire Venezuelan crisis and observe the reaction of its criollo and mestizo political class. They are, in effect, begging for foreign intervention. From a Spenglerian perspective, this is not merely a political stance; it is the definitive symptom of a post-cultural condition.

In Spengler’s morphology, a true Culture is an organic entity born from a primal landscape (Ur-landscape), with its own unique soul, symbols, and internal destiny. It grows, flourishes, and eventually hardens into a Civilization—a phase of intellect, empire, and giant cities that is spiritually exhausted. The final, terminal stage is the “fellaheen” phase: a population that continues to inhabit the geographic shell of a deceased culture, living amidst its ruins but possessing no creative destiny of its own. It becomes history’s passive object, susceptible to being managed or “cared for” by external, still-vital forces.

Venezuela is a stark manifestation of this. Its political class are the inheritors of a transplanted Spanish Civilization that was severed from its original European Faustian soul, yet which failed to generate a new, autonomous American cultural organism. They inhabit a hollow artifact—the 19th-century Liberal Republican state, a potted plant with no deep roots in this soil or soul.

Therefore, their cry for foreign intervention is the logical action of a fellaheen people. Having no generative political will, no internal cultural unity to draw upon, they instinctively look to external, still-active Civilizational powers—be it the US, the EU, or others—to impose order, solve their crises, and provide the structural framework they cannot generate from within. It is not a call to arms for a new destiny; it is a plea for a more competent caretaker of the ruins.

In Spengler’s terms, this is the end of the line. It confirms, with devastating clarity, the core thesis of this entire reflection: the rupture of 1492 and the failure of the post-independence project did not forge a new cultural organism. It produced a historical space populated by what Spengler would identify as a fellaheen population —forever looking outward for the political form and the vital force it lacks within, eternally twice removed from any yesterday that could have been its own.

When I see videos of the Temple of the Sun in Peru, I’m fascinated because I understand what it represents in Spenglerian terms.

What you are seeing is the Springtime of a Culture—the explosive rise of its primal symbols. The creative epoch when a new world-soul is born—occurred millennia ago on American soil. Everything they built, they owned. They authored their own blueprint for reality. We will never, ever, ever experience that.